Implementing Product Management in the Federal Government

In this blog, we continue from previous ones in extrapolating how product management can be contextualized and implemented in the federal government. We will tie this all back to the Policy on Results.

Note: This blog will link to internal ESDC documents, which are unfortunately only accessible within ESDC corporate network.

The Policy on Results sets out the fundamental requirements for Canadian federal departmental accountability for performance information and evaluation. It’s what requires departments to produce their Departmental Results Framework (DRF) containing an inventory of Programs Information Profiles (PIP). Two key pieces of information contained in a PIP are the outcome(s) and performance indicator(s) used for public reporting in the GC Info Base.

If we want to know what “products” a particular federal department produces, the clues would be in its PIPs. One of ESDC’s main products, we claim, is benefits. Services like Employment Insurance, Pension, and Old Age Security help Canadians navigate the eligibility and adjudication processes to get those benefits. With the new Policy on Service and Digital, these important services are intended to be delivered through digital means first (i.e. online).

PIP indicators are more social economic in nature than software delivery indicators (e.g. % of CPP contributors receiving benefit payments, number of persons with disabilities with enhanced employability, number of beneficiaries receiving education saving grants). Because Programs’ activities have a more abstract and indirect influence on their strategic objectives, programs use Logic Models to illustrate this “clear line of sight” between necessary enablers (e.g. activities like information outreach) and strategic objectives (e.g. seniors having basic level of income)1.

This complexity that Programs have to deal with has increased due the new Policy on Service and Digital, which intends to reflect citizen expectations by “digitizing” government business operations.

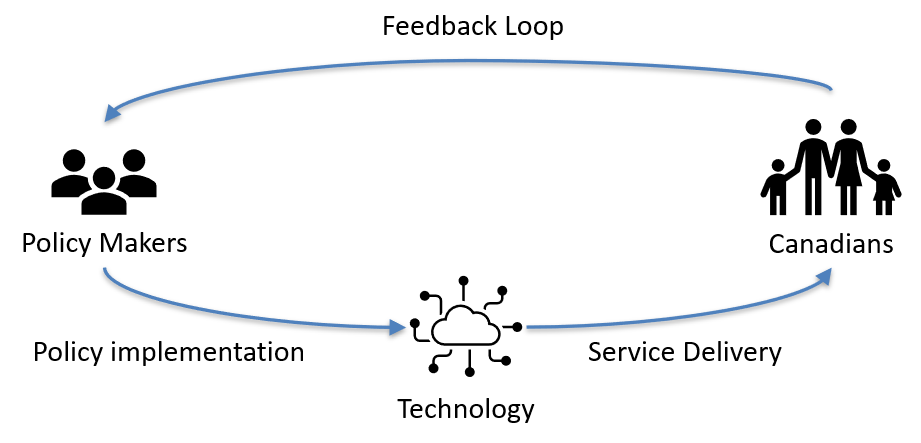

While complex, the move towards digital service delivery also presents an opportunity by resetting policy, delivery, and evaluation. With digital service delivery, Programs can more quickly obtain evidence to inform their improvements. This warrants us to adjust our planning methods by moving from advanced planning and rigid plan execution to one that rewards empirical cycle of trying, observing, and correcting2.

Figure 1. Digital presents an opportunity to shorten the feedback loop between Policy Makers and Delivery

Figure 1. Digital presents an opportunity to shorten the feedback loop between Policy Makers and Delivery

More concretely, we mean doing smaller, more frequent changes. Moving at the pace of relevance.

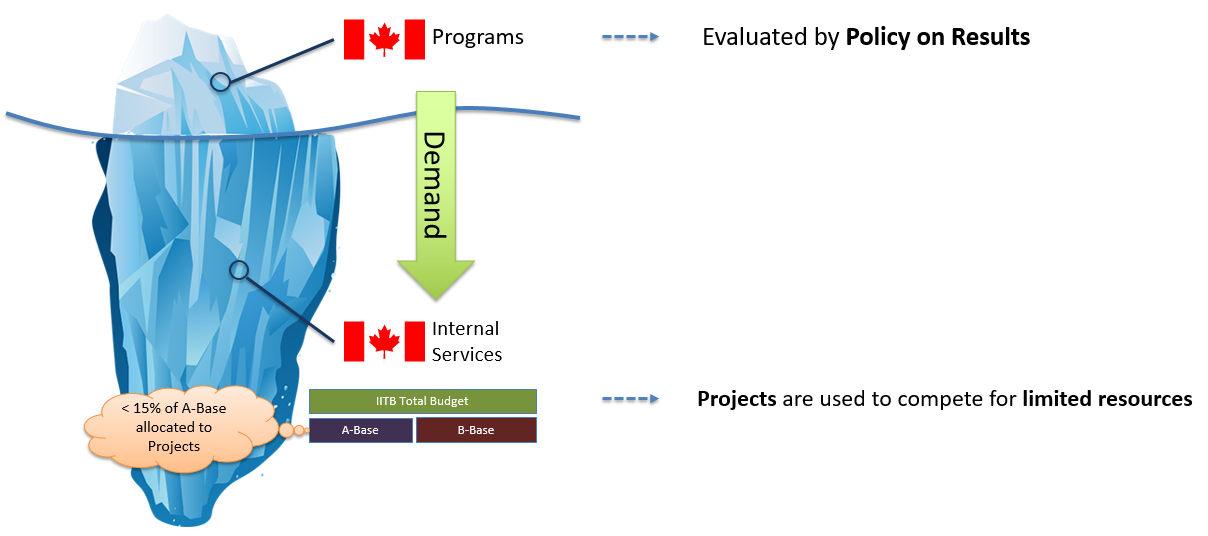

Digital service delivery means using software. However, the current DRF format has a gap: it treats software (i.e. IT) as an “Internal Service”. Although Internal Services are understood to be horizontal in nature, they can unfortunately be interpreted has a “back office function”3. This disjoints “IT” too much from the Programs. We all feel this gap when Programs compete for IT’s attention and limited resources, currently only known to be done as Gladiator-style project submissions (or worst, under the table deals that eats up our precious staff’s time and is unseen by decision makers).

Program Officials’ incentives are results. While CIOs’ and CFOs’ are about corporate integrity, including prioritizing over limited departmental resources.

Figure 2. The relationships between Program Officials, the CFO, and the CIO4

Figure 2. The relationships between Program Officials, the CFO, and the CIO4

Because each officials are bound by a different set of rules (the Policies they are being held accountable to, like the 411 requirements for CIOs, their behaviours and perspectives of each other understandably differs.

This conundrum can be understood by the typical iceberg visualization.

Figure 3. Lots of stuff under the surface that Program Officials may not see (and don’t need to care about)

Figure 3. Lots of stuff under the surface that Program Officials may not see (and don’t need to care about)

If, in their periodic program renewal activities, Programs do not seek sufficient funding to sustain their digital operations, it affects their results. And when TB funding requests are predictably answered with a reduced budget response, difficult prioritization decisions need to be made (e.g. number of employee laptops procured and maintained, labour costs to make changes to software systems).

The current method to prioritize work is to bundle it as projects, and then compete these projects for the limited resources of the organization. This creates a lag for delivery.

And to get results, delivery matters.

ESDC counts 50 programs grouped in 5 core responsibilities. For common IT services needed to deliver on those programs (e.g. software application development on the benefit payment system), the competition is fierce. Multiple projects collide for IT commitments. The bigger the projects, the further in the future the commitments are sought. IT’s internal capacity spends a great deal of time managing this overhead and dealing with the inevitable changes that a complex environment like Digital Transformation brings.

If you’re being invited to three concurrent virtual meetings, all having 70+ participants, it is a symptom of the organization struggling to maneuver in this complexity.

Towards a different method to fund, prioritize, and align work to Programs’ agenda

Continuing to improve the resulting product that a project created requires sustainable sources of funds (e.g. to pay staff). Transitioning to product management post-project reduces management overhead and should incentivize Programs to seek sufficient funding in their program renewal to sustain their product’s life cycle, and strategically plan the improvements needed over a time horizon.

The new Policy on Service and Digital integrated planning requirements promotes this method of thinking (section 4.5 on identifying mission critical applications from their respective APM portfolio).

Product Management5 seeks the following tactical changes:

- Reduce funding lag

- Budget portfolios of products (value stream teams)

- Provide new assurances for investment decision makers

- Adjust IT’s financial model

Reduce Funding Lag

In a product-based funding model, the sizes of the changes are purposefully kept small to avoid an investment being stalled in a planning stage for too long (promoting the adoption of DevOps, sharing software components, and interoperability between solutions).

The Investment intake process changes to consider this new type of funding model: product-based.

Criteria are established to guide investment decision makers on whether a particular investment proposal is ripe for this new funding model approach (similarly to block funding). Some of these criteria could include:

- It is likely that the investment will remain a departmental priority for a minimum of three years6

- It involves a solution that requires regular iterations until maturity, retirement, or replacement is achieved (i.e. its requirements are expected to change based on user feedback)

- It can commit to deliver periodic business outcomes (in the form of production changes) that are tied to a Program’s performance indicator, typically using a cadence of less than 3 months7

- Has cross-functional team(s) from both Business and IT, for the development and operation of the solution.

- Has established a yearly Business and IT budget with sources of funds secured

These criteria also serve as terms and conditions for this investment. Consequences of non-compliance (e.g. inability to keep the agreed schedule cadence) may result in losing the product-based funding.

Investment intake classification will need to provide funding priority over a multi-year horizon so that the product team does not have to use its internal capacity to re-ask permission year over year for funding. The time horizon should map to existing authorities provided (e.g. Treasury Board submission approvals, departmental plans). An exit strategy should be produced for when the product-funding ends (addressing things like team member reallocation to projects, or to sustain other products).

Budget portfolios of products (Value stream teams)

Products are grouped into portfolios and managed by dedicated value stream teams. Teams are responsible for both the development and operation of the products.

Budgeting is not done at the product level, it’s done at the team level (who will most likely manage more than one product in the portfolio). Budgeting is a joint Program Official and CIO agreement, enabled by clearly identifying the sources of funds that will sustain the value stream teams. The Budget may come from Program sources of funds (e.g. Pension Program) and the CIO’s A-Base budget (sourced from the GC Consolidated Revenue Fund).

The team budget helps create boundaries for the Program Official to make difficult prioritization decisions. Decisions that essentially dictate focus for the value stream teams within the portfolio of products they manage. Should the budget need to be increased, corporate governance is needed (i.e. financial pressures at the departmental level).

Provide new assurances for investment decision makers

Project assurances are used by the investment decision makers to assess, using evidence, a project’s adherence to policies and practices. This evidence currently takes the form of project gating artefacts (e.g. business case, project charter, project management plan, requirements document).

A product-based funding model still has gates, but its process is different. Investment decision makers will need other kinds of assurances that Product Teams are using public funds in a responsible manner.

A Product Lifecycle Process is cyclical. It has a start (creation) and an end (decommission), but its middle is a series of periodic continuous improvements.

The proposed product-type assurance is mapped to four Product Lifecycle Process steps:

- Gate 1 – Intake: the artefacts used to justify the product-based funding model (e.g. multi-yearly budget costing, the value stream teams involved, sources of funds, agreed schedule cadence, Architecture Boundaries)

- Gate 2 – Review: a periodic cycle in a product-based model to review the product’s value and enterprise alignment (e.g. involves a Product’s outcome-based roadmap, Yearly Budget Costing, Key Product Metrics focused on performance indicators change, Architecture Boundaries).

- Gate 3 – Continuous Improvements: the series of releases the product undertakes. It includes approvals to deploy, acceptance reports, and product workload metrics.

- Gate 3 Updates: during the continuous improvement step, Product teams perform periodic updates, such as bi-yearly, to corporate committees (e.g. investment board, enterprise architecture review board).

- Gate 2 Reviews: every X years, Product Teams are expected to go back to Gate 2 and perform product reviews. A review expects some changes (e.g. Architectural boundaries, product roadmap).

- Gate 4 – Decommission: the end of life of the product.

These gates represent assurance evidence only, and do not completely reflect the work that a Product team would do (such as evaluating a previous release using data analytics to inform the product’s strategy and roadmap evolution).

Adjust IT’s financial model

IT’s financial model is somewhat different than Programs because work that an IT practitioner does is not necessary tied to a single authority or program (or even to a single product!). Therefore, different methods are used to show accountability to parliament when IT expenses, such as staff labour, are used.

Do you use timesheet codes every month? If yes, that is one of the reasons why.

The current method we use to compute work is by project (different timesheet codes are created by projects, or by operational activity for maintenance). In a product-based funding model, we concern ourselves with the aggregated expenses on the life span of a product, and where the authorities for those expenses came from. This affects Financial Management Advisors (FMAs) work when performing attestations that Product Teams are consuming and reporting financial information correctly.

IT’s financial model is adjusted as follows:

- Indirect costing

- Represents the Product Team’s multi-year budget (salary and non-salary).

- The budget has allocations in terms of different timesheet codes (see direct costing). The Product’s roadmap informs the timesheet codes creation for each outcome.

- Indirect costing also includes common and corporate services that a Product Team may consume (e.g. employee benefits, common cloud services, equipment like laptops).

- Direct costing

- Represents the cost that is unequivocally attributed to a single cost object: the product (comprised of labour work, infrastructure like SSC and Public Cloud subscriptions, and technical stack software licences)

Indirect and Direct costs are paid by different sources of funds (that need to be secured by a joint CIO and Program Official agreement).

Towards an even greater ambition

Expanding further the product management concept, we would seek to ensure that any investment touching a particular “product” (e.g. a Pension System) be considered as an investment using product-based funding.

This would bring stability to the Pension System teams (including Program Areas) by having them commit to only one plan: their product roadmap.

Any investments (e.g. projects) seeking to make changes to the Pension System would, in fact, seek to make changes to its product roadmap. Those projects would compete between themselves not on the availability of IT, but on which changes are needed NOW and which are needed LATER. It brings the conversation out of IT and into the Program areas, moving the prioritization exercise to a strategic and tangible one by breaking down what is needed into smaller, more manageable changes.

This Product Roadmap would still require having a faster-than-usual cadence otherwise it risks creating a bottleneck to backlog changes. Further promoting smaller, less risky changes for IT to handle.

Other blogs on this topic

- Transitioning to Product Management by following Job Bank

- The Problems with Project-Based funding for IT organizations

- CIOs and CFOs are essential in making digital transformation a reality

- We are inadvertently promoting risks in IT

Notes

-

Logic Models have similarities with Investment Logic Maps, recommended to be used by our Directive on Benefits Management as a means to comply with the Policy on Planning and Management of Investment. ↩

-

Mark Schwartz, War & Peace & IT ↩

-

Images with non-commercial licences taken from emojipng.com, pngegg.com, flyclipart.com, imgflip.com ↩

-

We’ve interviewed different federal departments and the industry to get a good enough grasp of what “product management” means. We can confidently say that there are no standard meaning. If two people saying they know what product management is talk to each other, they will hear different things. ↩

-

Different sources may be used: parliamentary budget, departmental plan, MAF, major events (e.g. pandemic crisis) ↩

-

While there is no standards, this number was used based on interviews with existing federal government teams that operate in a “product” fashion and industry articles on the subject (e.g. Gartner) ↩