CIOs and CFOs are essential in making digital transformation a reality

In this blog, we suggest that Chief Information Officers (CIOs) and Chief Financial Officers (CFOs) are essential to bring a Digital Transformation vision into a reality. Although Digital Transformation deals a lot with changing business operations, if technology releases are not able to push through, that vision will remain a dream and will not manifest itself. We will show how critical CFOs are in allowing technology to respond faster to continuous business changes, and how Cloud and DevOps are opportunities that cannot be overlooked.

Note: This blog will link to internal ESDC documents, which are unfortunately only accessible within ESDC corporate network.

What Digital Transformation Entails

On April 1, 2020, Treasury Board’s (TB) Policy on Service and Digital came into effect, which serves “as an integrated set of rules that articulate how Government of Canada organizations manage service delivery, information and data, information technology, and cyber security in the digital era.” The Policy supports the mandate of the Minister for Digital Government and is guided by a commitment to the guiding principles and best practices of the Government of Canada Digital Standards.

As the Policy’s requirements target Deputy Heads, we look at its associated Directive for requirements targeting the senior officials designated to be responsible for leading particular functions (i.e., IM/IT, Service, and Cyber Security). Here are some statistics the IT Strategy team did (link to source data):

| Official | % of Total Requirements | Mandatory Procedures (4) requirements |

|---|---|---|

| CIO (w/ Chief Data Officer) | 84% | 229 |

| Service | 10% | 0 |

| Cyber Security | 6% | 74 |

With such a focus on CIOs and CDOs, TB formally recognizes the ubiquitous nature of technology in delivering services to Canadians. Because CIOs and CDOs are accountable for such a large number of requirements, we claim they also need to be in a position to determine how technology investments are to be managed (a domain historically attributed to CFOs).

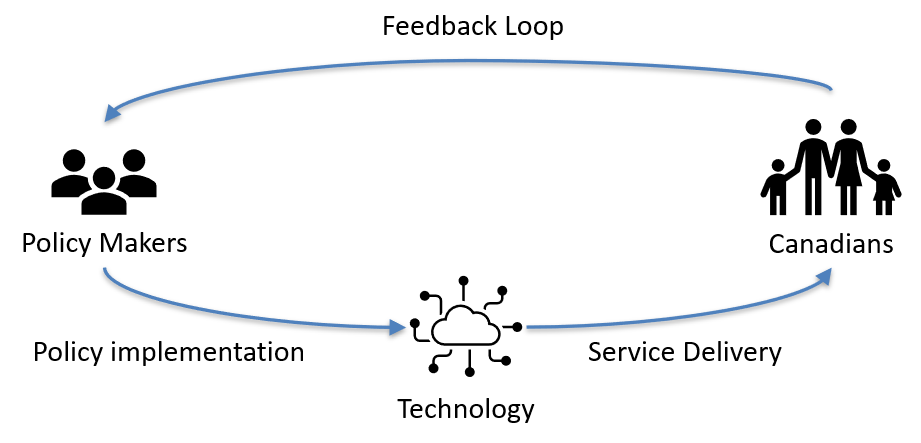

Elected officials now recognize that technology is at the core of service delivery. This means that in order for policy makers to affect Canadians, they will need to go through technology delivery. If technology is not responsive enough, the lag between policy making and service delivery will directly impact the ability of departments to fulfill their mandates (which did happen in the past and made front-page news). Policy makers looking for data to inform their evidence-based decisions (i.e., user feedback loops) will find it stored in databases, managed by software.

At ESDC, we find the above explanation articulated as the Business Delivery Modernization’s (BDM) 2nd main objective: Policy Agility.

We want to look at this relationship with technology closer, and how things have changed in the last few years that present new opportunities for us (hint: we’ll be talking Cloud and DevOps).

How Are We Managing Technology Investments

Using technology is a risky and costly investment.

CFOs look at the TB Policy on Planning and Management of Investments to establish investment management governance “to ensure that these activities provide value for money and demonstrate sound stewardship in program delivery.” The Policy’s associated Directive on the Management of Projects and Programmes is where we find the notorious project gating process “so that the expected benefits and results are realized for Canadians.”

We narrow the goals of these financial policy instruments to two main ones:

- Managing risks

- Placing investments where there are benefits

We want to look closer at #1 especially when our 2019-2020 Departmental Plan states that “The Department […] recognizes that one of the biggest risks it faces is a failure to take risks.”1.

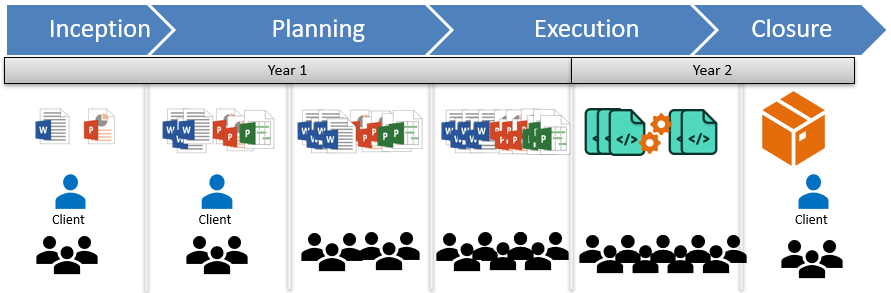

The current gated method to manage technology investments seeks a high degree of future predictability. Before work on software can start, we seek clarity on requirements and the effort needed to fulfill them. This usually takes form in producing multiple documents, aggregated as an overall plan before approval to execute can be obtained. There was a time when this made perfect sense as it was expensive and time consuming to procure servers, code software changes in a procedural language, test those changes on dedicated testing servers (sometimes shared with other software projects so that risks of project collisions also needs to be managed), burn the updated software on a disc along with installation procedures for someone else to execute (so segregation of duties can be respected), and expect downtime when those changes are being applied. If a client changed his mind during this execution phase, the impact to the project was high.

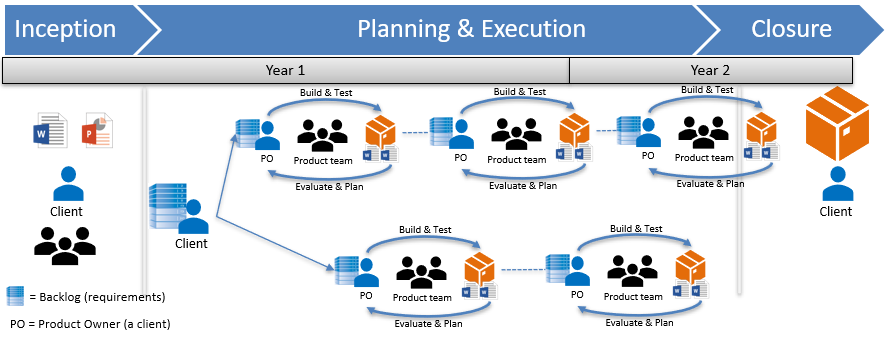

Figure 2. A high-level view and interpretation of the current Project Management Lifecycle using gated decision points

Figure 2. A high-level view and interpretation of the current Project Management Lifecycle using gated decision points

The bigger the project, the further into the future we require to foresee. This approach comes with a few challenges:

-

Accurate foresight is extremely rare: There are statistics and reports regarding the low success rates of large projects2. Though we think those are not necessarily about success rates. They are about the reality that change is inevitable, that having such foresight is extremely rare, and that it is nearly impossible to plan that far into the future.

-

A business case is thought of as an expectation, instead of a hypothesis: The benefits realization at the end of a project is not a sure thing. A project may be delivered on time, on budget, as per requirements, but yield negative outcomes. The longer the organization is locked in a project, the greater the risk of being locked into a potentially bad idea.

-

It puts IT in a passive state: “I need requirements” is something you probably heard your IT teams say to you. This should not be surprising as we are framing the organization to behave as such. The Government’s pandemic response is an exception to this statement where personnel worked creatively together in a time of crisis.

-

Progression is measured with documents, instead of working software: If after 18 months of work and $2M spent we do not have working software to show for, would we consider it a good investment?

Only successful projects, in production, enable the organization to gain empirical evidence necessary for their evidence-based decisions.

Opportunities for change

The digital world brings a high level of complexity and uncertainty with it. This should warrant us to seek very different approach to carrying out initiatives. A predictable world rewards advance planning and rigid plan execution. But a complex and uncertain world rewards an empirical cycle of trying, observing, and correcting.3

New methods of developing software are available, mainly Cloud and DevOps, that warrants us adjusting our investment management methods. With them, the time-consuming efforts of procuring servers, coding, testing, and releasing to production mentioned above are dramatically reduced. An opportunity exists to leverage this speed, try things out before we commit to them, and more accurately inform planning decisions.

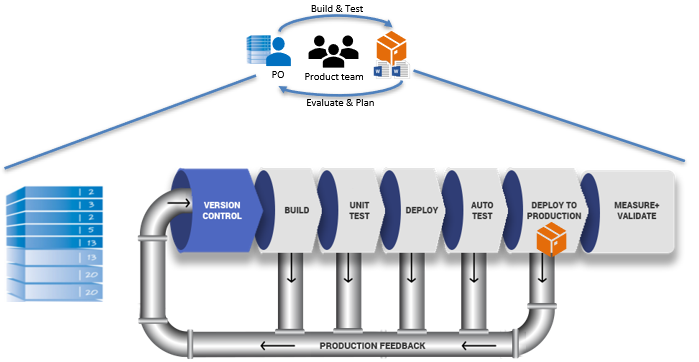

The conventional sequential thinking of planning, then executing, changes to one that is cyclical. Planning and Execution become symbiotic where both inform each other over smaller time horizon periods.

The result enables the use of empirical data to make planning decisions. Through execution, we can inform the next planning time horizon for the initiative. We can measure progress through actual working software, as opposed to planning documents often containing many assumptions. We can make “Decisions […] based on an assessment of full life-cycle costs and demonstrate value for money and sound stewardship;”4.

In the first example above (Figure 2), we obtained one software release after 18 months. Whereas in the second example (Figure 3), we could have had five releases in that same amount of time (should we have decided to release them in production). Through each iteration, the Client, the Product Owner, and the Product Teams all learned a little bit more about the user needs, the complexities of adapting the software to those needs, and the technical debt accumulated throughout that time. This information is used as empirical evidence to plan with more accuracy the next iteration cycle.

These fast Product iterations are enabled by DevOps (powered by cloud technologies).

This opportunity is available should we first understand how different software is from other types of investments. Mainly that software consists of an assemblage of many components5, each potentially able to work independently from each other, and that provides services to one another (we then start seeing that machines are also users). Breaking large IT Solutions into more manageable parts (whether called IT Products or Applications, sometimes compared to Lego blocks) means work by multiple teams can start without the need to have figured out the whole puzzle in advance or how to solve the problem in one single piece. If you heard the term “Monolith”, it’s what we strive to move away from as it impedes our ability to respond fast and is too often the cause of project collisions.

The above planning-execution symbiotic relationship should be allowed as per the following TB Directive on Management of Projects and Programmes requirements:

(welcome change) 4.2.6 Ensuring where business change is required to achieve the business outcomes, that the project and programme scope of work includes all the activities and outputs necessary to bring about this change

(be iterative and agile) 4.2.8 Applying as appropriate, incremental, iterative, agile, and user-centric principles and methods to the planning, definition, and implementation of the project

(make evidence-based decisions) 4.2.18 Establishing a project gating plan at the outset of the project, consistent with the department’s framework, that; (4.2.18.1) Documents the decisions that will be taken at each gate, the evidence and information required in support of the gate decisions, the criteria used to assess the evidence, and the gate governance

Currently, TB only provides directives and guidance regarding Project and Programme Management, leaving departments by themselves in adapting existing Project Management practices to a Product world. This is where we see a strengthening of the CFO - CIO relationship.

The ESDC IT Strategy team is interested in finding other departments looking at the same challenges, whether they are working towards solving them or even have found the solution.

Some Work In Progress at ESDC Fostering these Opportunities

The ESDC IT Strategy team is currently working on a set of strategies to move the organization towards reducing risks associated with technology in order to accelerate business flexibility.

- Target IT Solution Delivery Model: a strategy to move the organization towards same day software deployment in order to dramatically improve service delivery agility.

- Adopt, Build, Buy: a strategy that seeks to resolve the oversimplification approach of buying or building software.

- Continuous Improvement: a strategy to transform ESDC into a high-performing organization through the continuous improvement of daily work.

- Micro-Acquisition (GCDevExchange 2.0): a strategy that seeks to provide the department and suppliers with a lightweight, low dollar value (< $10k) contract amount, acquisition process.

References

-

2019-2020 ESDC Departmental Plan, page 11 ↩

-

The Standish Group Study, 5 Auditor General Reports (2006 Novembre, 2010 Spring, 2011 June, 2015 Spring, 2018 Spring), and the June 2016 and May 2019 House of Commons questions on large IT projects over $1M ↩

-

Mark Schwartz, War and Peace and IT, IT Revolution, 2019, page 30 ↩

-

TB Policy on the Planning and Management of Investments Expected result #3.2.2 ↩

-

Appendix A - Business Case (Diagnosis) of the Adopt, Build, Buy Strategy ↩