Transitioning to Product Management by following Job Bank

In this blog, we continue to extrapolate on how product management can be implemented within the federal government, particularly in the digital space.

We will follow how Job Bank1 is transitioning from project to product by being provided with the necessary environmental structure to work in. We can tie this back to its program desired outcomes.

Note: This blog will link to internal ESDC documents, which are unfortunately only accessible within ESDC corporate network.

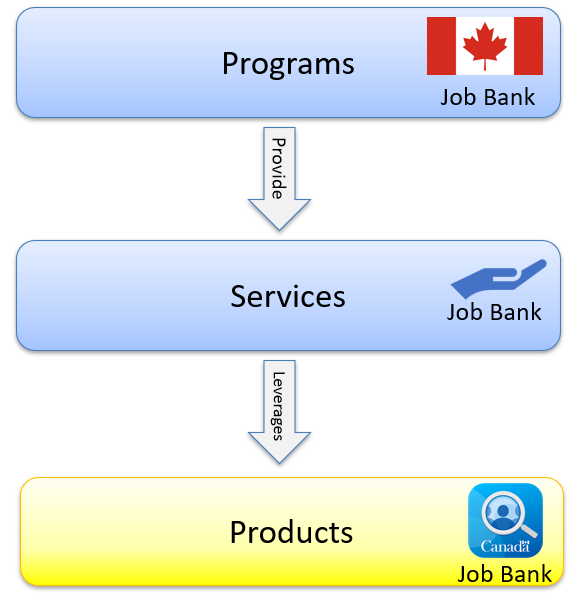

Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) is a service department, as are the large majority of Government of Canada departments. ESDC provides its services via 50 Programs to improve the standard of living and quality of life for all Canadians. One of those programs is Job Bank.

This is how we tie product to service and then to programs.

Programs provide services. A service consumer doesn’t care about the costs and risks to operate the service, but a service uses products, which do have a cost, for its delivery. Managing the internal complexities to sustain these products, and how they affect the service level is where product management fits. Moving to digital means some of those products will be exposed to service consumers (e.g., a website, a mobile app).

The words “Job Bank” can be understood to mean three separate things:

- a program;

- services to job seekers and employers, ultimately measured using the program’s Performance Information Profile (PIP); and

- a family of products - most notably eleven of them making up its website, which is exposed to and consumed by clients as part of Job Bank’s service delivery.

Interactions with the website have a direct impact on the service performance (e.g. ability to navigate and find information, being correctly matched to a relevant job, etc.), and gives rapid insights for improvements as interactions with software generates large amounts of data. This is the new opportunity that digital brings: the ability to quickly act on those insights, using evidence-based decision-making. All with the objective to improve results.

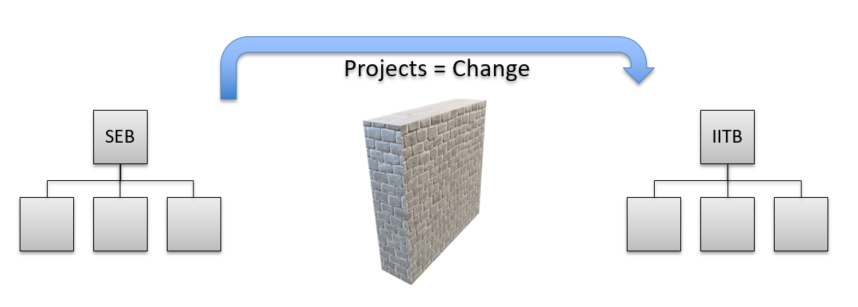

In the traditional program-corporate relationship, IT barely gets enough funding to “keep the lights on” and projects are used when programs want to engage IT staff to make software changes. This can create unnecessary lag for much needed small improvements.

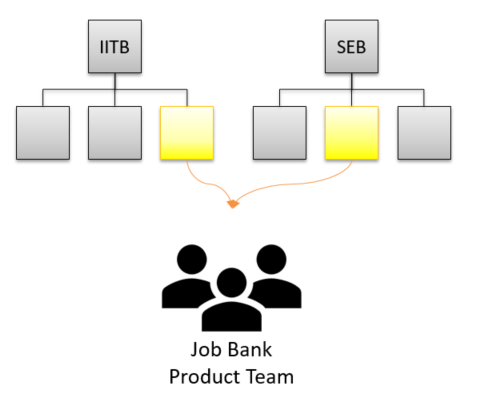

In the digital world a departmental product “team”, like Job Bank, should embed both business and IT staff. However, because Treasury Board (TB) Policies regulating programs and corporate2 put different persons in charge of IT and program functions, these two separate persons will naturally want the staff responsible for their function in their respective org charts.

Who can blame them! If your job (and executive bonus) is on the line for function X, you’ll of course want to oversee any work done on it. The Job Bank Program staff sits in the Skills and Employment Branch (SEB), while the IT staff sits in the Innovation, Information, and Technology Branch (IITB). The Job Bank Program team launches projects at IITB when they need IT staff to change the software used in the Job Bank Program delivery.

This is where we want to differentiate improvements from projects.

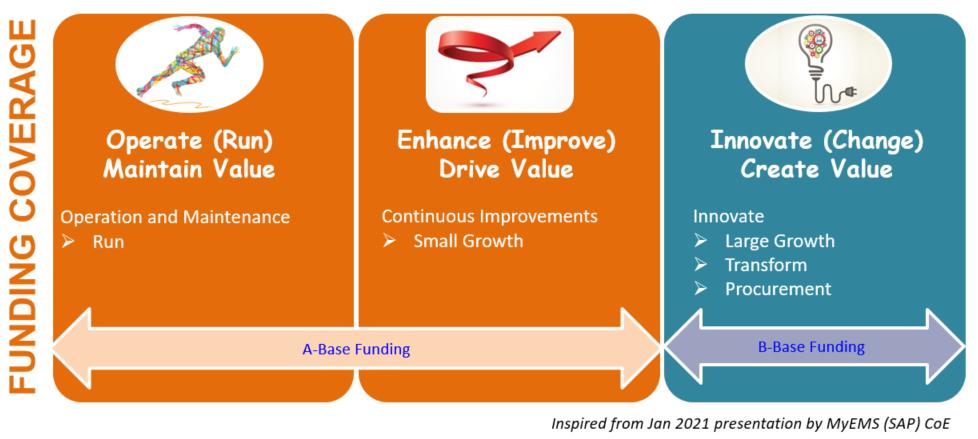

Funding for RUN activities continues to be used for “keeping the lights on.”

Projects (which definitely still exist in Product Management) are used to coordinate large change such as changing the enterprise through a transformation or needing to coordinate change over multiple products.

In the middle, though, there is an opportunity to allow rapid, small, changes to software, enabling continuous improvements. Typically, this would occur on existing business processes, to enhance user experience, and continuously address cyber security risks.

Some specific roles, skills, and structures are necessary to enable such continuous improvements.

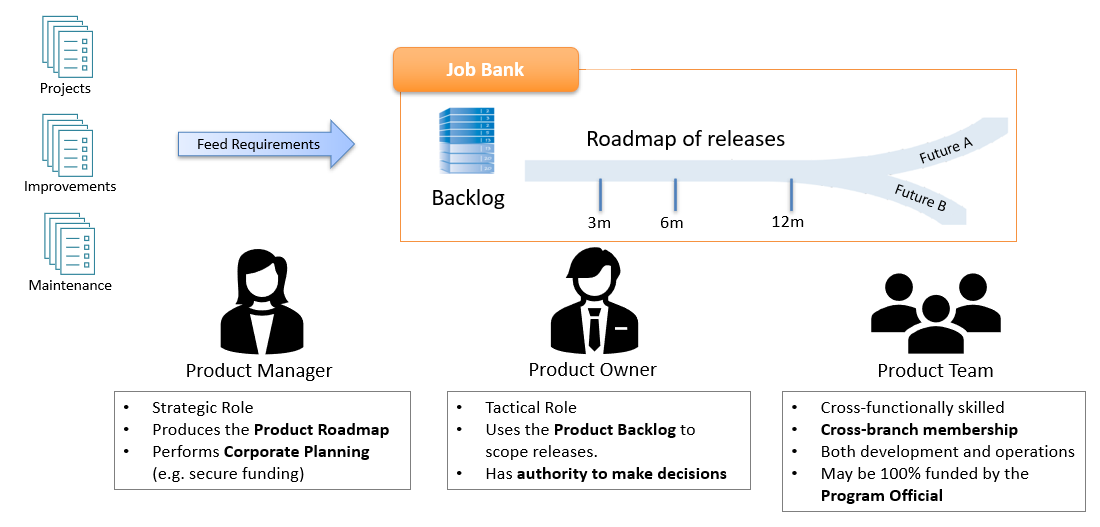

The different kinds of work affecting a particular product are essentially requirements feeding that product’s backlog. Product teams perform their own improvements and maintenance activities, while external projects bring work to them.

Our pension system is a good example to use here. It’s bombarded by projects (whether business enhancements, technical debt remediation, software patching, legislation mandate, transformational initiatives). These changes come from multiple executives as the pension program is not tied to a single official overseeing its delivery. It can become unrealistic for IT alone to manage and coordinate this scale of commitments. Especially in dealing with territorial behaviours that projects may manifest (e.g., “I am TOP priority, this is MY budget, these are MY resources”).

To manage all this demand, product managers are used. It’s a strategic role. They look beyond a 6-month time horizon. The product manager uses the product’s roadmap as both a communication tool and a negotiating one. Collaborating with the different project managers on what is reasonable to do over a time horizon. The product manager also ensures the product team is well equipped to handle demands, such as performing financial, HR, and architectural planning. In particular here: securing funding.

Product owners are a more tactical role. They look within a 6-month time horizon. The product owner works closely with the product manager and the product roadmap to scope releases and has ultimate authority to make decisions on the product. They work with the product team to elaborate more detailed requirements from the roadmap’s high-level ones, and may engage other IT professionals when need be (e.g., IT Security).

We think both the product manager and the product owner need to sit on the Program side due to their business decision-making aspect. Though it is expected they will have to work closely with IT Managers to fully understand the implications of risks, such as creeping technical debt and cyber security, has on their product’s livelihood as well as ensuring compliance to IM/IT Policies (e.g. IT Security’s software patching requirements).

The product team is made up of cross-functionally skilled members, from multiple branches. This is the space where Agile and DevSecOps fit in. The faster pace of release necessary to avoid clogging delivery promotes their adoption. Product teams must be well trained in Agile, otherwise chaos can creep in and negatively affect their performance, or worse, communicate to senior management that “Agile doesn’t work”. Project management discipline is still actively used here, especially by the product manager, without necessarily formalizing all work to a departmental committee.

In this space, it’s normal that certain IT professionals can’t see beyond the backlog and do not have sufficient appreciation of all the planning work that projects have done to feed them (e.g., getting necessary authorities from Treasury Board, performing organizational change management).

We also see certain other roles being necessary, such as the IT Security Champion. This is because the pace of change expected, and the risks associated to even small software changes, warrants security expertise to be embedded in the product team. This further promotes equipping product teams with the right tools and even warrants delegating certain architectural decisions to product teams as they are the ones suffering the consequences of technology choice(s).

This is how we propose to fund cross-branch teams.

The program official needs to budget and identify their source of funds for IT work. This is not a job for Corporate to do. If a Program Official seeks to get a piece of the CIO budget they are essentially competing with 49 other programs over that limited budget and putting the CIO in an awkward place by having to make business priority decisions.

Instead, the program official needs to go to the source. For Job Bank, it’s the Canadian Employment Insurance Commission. In its periodic Treasury Board submission renewals, Job Bank needs to identify sufficient funding not just for its program staff, but also for IT work.

Once IT funding is mentioned in the TB submission and approved, it can then be transferred to IITB and used to fund dedicated IT staff for that program (staff that will remain in IITB). We see using Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) between the CIO and the Sponsoring Branch where the Program Official sits as an appropriate vehicle or document to solidify these arrangements.

We expect conditions over those funds, however. Such as spending them to generate outcomes, so … doing software releases rather than planning documents (those are for projects to do).

We also do not expect an Enterprise Architecture Review Board (EARB) to be involved in approving or endorsing such funding. This is because EARB is focused on the enterprise and improving an existing product has negligible effects on the enterprise. EARB is involved in projects.

These conditions and the trust level provided to product teams can be managed through a directive’s consequences of non-compliance, such as adding layers of governance during the product team’s yearly funding cycle.

It’s worth noting that projectization is still needed to coordinate work across product teams and to bring workload to them.

To increase a product team’s capacity, existing funding pressure instruments are used (e.g., if a $2M/year product team can’t meet demand for a given year, departmental funding pressures can be used to increase it to $4M/year). For a cross-branch product team funded by a program official, this funding pressure should be done to the program official’s branch.

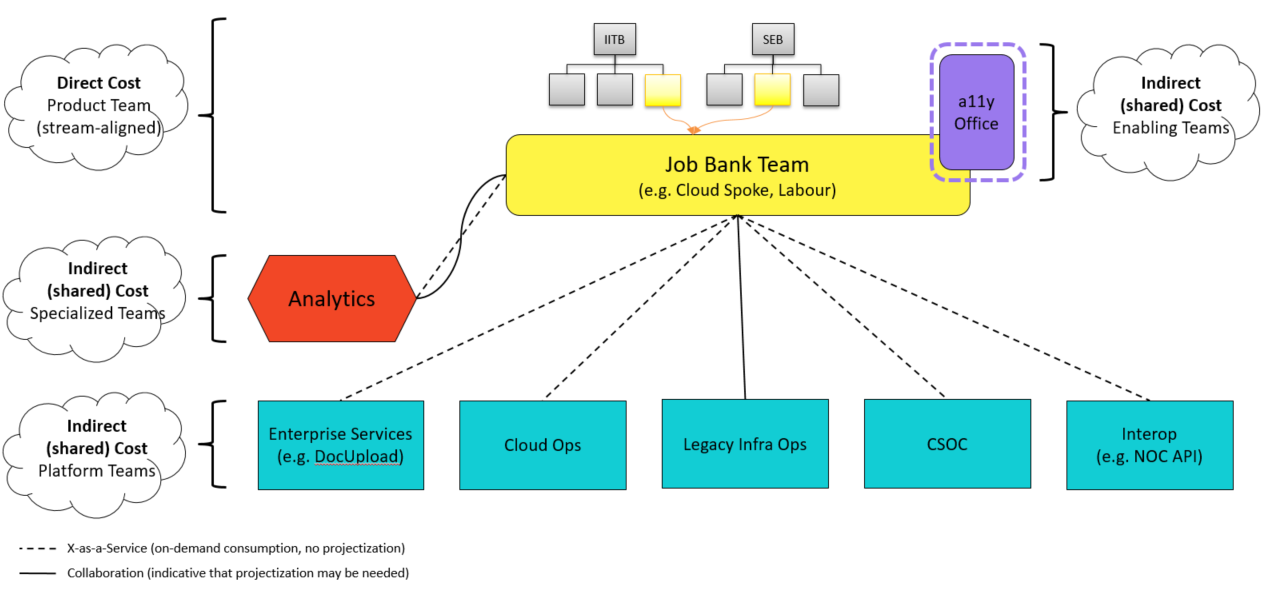

This team doesn’t operate on an isolated island, though. It collaborates with other IT teams.

Team Topologies concepts are used to explain interactions with other teams.

There are four types of teams that interact. The stream-aligned team is what the program official is funding. Its cloud credits and labour costs can be directly attributed to the program.

The other three types of teams cannot be directly attributed to a single program, their costs are essentially shared, making up the “IT Corporate Services” space. Their members will most likely all be under the IT organization but there can be cases where they may also have members from more than one branch. Their funding and sustainability require pooling funds into the CIO budget. Unless they can provide on-demand services, such as via an API, their engagements may need to be projectized as stream-aligned teams would essentially be competing for their time commitments.

Specialized teams provide significant expertise in some areas. For example, relational database performance, advance data modeling, mathematics and calculations. These teams are typically first engaged as part of projects, then continue by providing services (e.g., setting up a Business Intelligence (BI) COTS product for the stream-aligned team then letting them manage the BI’s reports).

Enabling teams help other teams overcome obstacles. They coach and mentor them until they’ve gained sufficient expertise, at which point they step away. Enabling teams are temporary in nature. The example above is the Accessibility Office.

Platform teams provide compelling internal products and services to accelerate delivery by stream-aligned teams. One example for Job Bank is that it uses a DocUpload service that allows clients to upload documents, which then performs anti-virus scans and stores them securely. Re-using such service enables the organizations to save time and money.

We can then see how Loose-Coupling Architecture (i.e. API-driven) adds great value as it grants more autonomy to teams, reducing the need to projectize by providing on-demand services.

Final Thoughts

Obviously, we have not covered everything that product management entails, such as vision setting, user research, and the different phases a product goes through in its life cycle. This is well documented, such as on PMI.org or PDMA.org.

The Job Bank team is mature in applying product management philosophy, for example by performing release impact analysis which evaluates, using empirical evidence, whether a particular release got them closer to a particular goal and if course corrections are needed.

Job Bank is also not just a single product, but a family of products. We could increase the level of granularity by breaking each product down to sub-products and to an atomic level: a software library. But then we’d get into an argument about external vs internal products…

What this blog sought to do is share how we’re striving to create the necessary space for people to interact as one team, even if they may be from different branches, and avoid unnecessary hurdles for much needed collaboration to take place.

We are formalizing how such a transition can take place via a Pilot Product Management Framework (consisting of a directive and an associated standard). The framework is currently in peer review internally as we want to use it for two Pilot projects: one with Job Bank and one with the MyESDC mobile app.

Notes

-

The Job Bank program is actually part of the Employment Insurance Act, providing free bilingual services to employers and job seekers as a means to alleviate stress on the Employment Insurance program. ↩

-

These TB Policies are how a rules-based society, that our democracy is founded on, works. Choosing to ignore these rules is indicative of a government going rogue. Our public service function is to upheld the government’s integrity and accountability in that area. ↩