The Problems with Project-Based funding for IT organizations

In this blog, we highlight how the traditional project-based approach to funding and management of technology investments is hurting IT organizations and, as a consequence, departments’ ability to iterate and improve frequently. This is a continuation from a previous blog where we suggested that Chief Financial Officers (CFOs) are essential in bringing a Digital Transformation vision into a reality.

Note: This blog will link to internal ESDC documents, which are unfortunately only accessible within ESDC corporate network.

Some Data

In ESDC’s Project Centre we see that there are 103 IT-Enabled projects in progress1, with 101 of them requiring a Treasury Board Submission (TB sub). Not all projects are large in nature, in fact 61% of the 101 TB subs are for projects under $5M, with 29% being for under $500k.

Small projects are good. As per the Standish Group’s CHAOS reports (standishgroup.com/sample_research_files/CHAOSReport2015-Final.pdf), small IT-Enabled projects have a much higher resolution success rate (resolution = on time, on budget, with satisfactory results). But we believe the burden of our current funding mechanism inadvertently promotes risky behaviours.

A sample of 26 IT-Enabled projects2 shows that it takes, on average, 1,291 days for them to start their execution stage. Meaning the IT organization, on average, starts development and testing of the IT solution only after 3.5 years from the project’s inception.

The effects projects have on the IT organization

We understand that TB subs are necessary for obtaining expenditure approval and additional funding3. In addition, because software is essentially a collaborative process involving many teams4, projectizing the work is often seen as necessary to formalize engagements between individual IT teams and coordinating that work to completion.

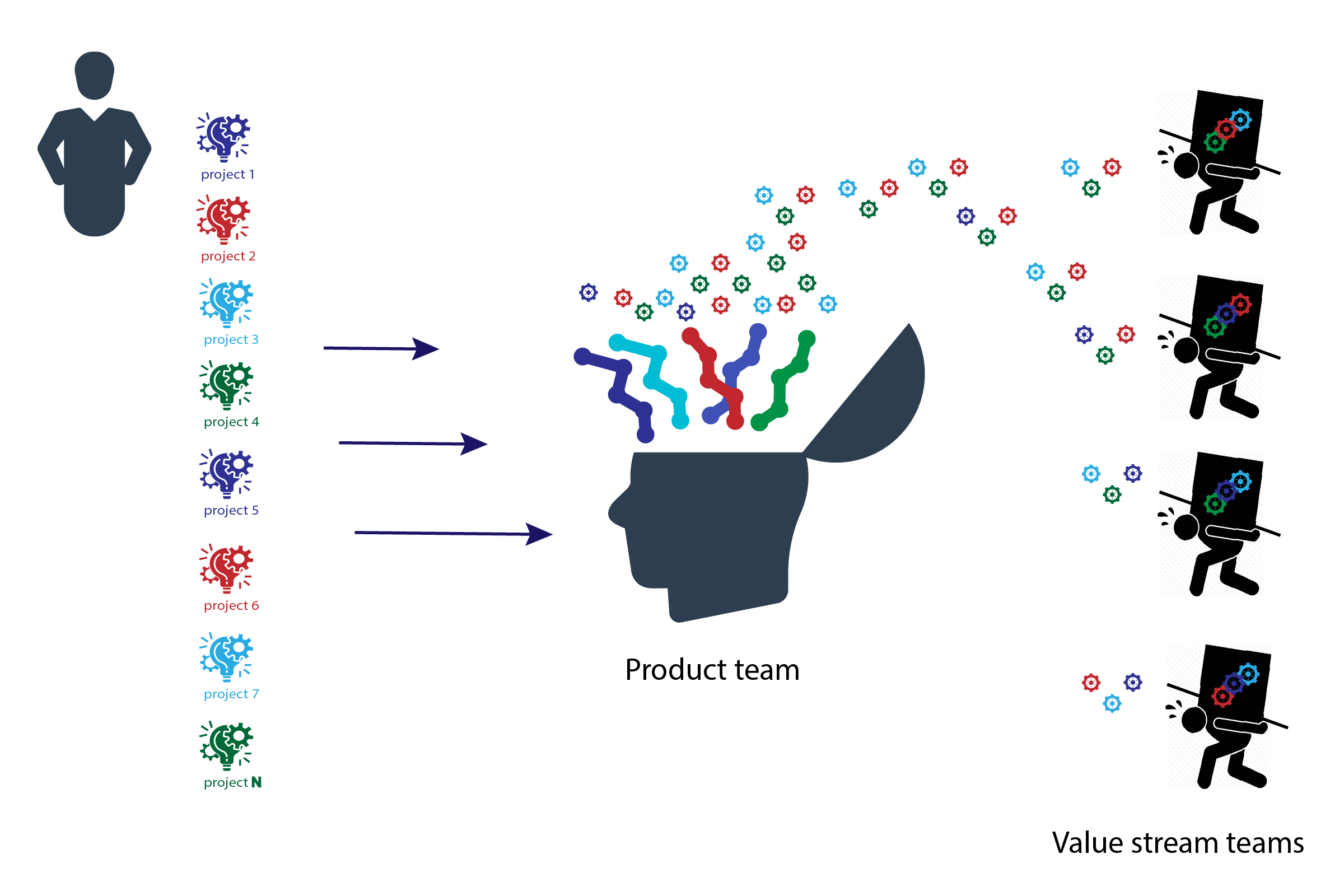

Projects are therefore used to compete for funds. Funds used for salary and non-salary expenditures of multiple IT teams. In a sense, projects are used to compete for the IT staff’s prioritization of work. The problem happens when you have a large amount of advance planning, bundling of various work affecting large scale software applications, and the inevitable quarterly re-prioritization, all colliding on IT teams. An IT team responsible for a product is in a constant struggle to re-adjust its work based on changing demands in addition to providing long-term costing estimates to these individual projects. This product team will spend a great deal of energy on planning expectations of work with other peer IT teams5 to be able to fulfil commitments it made to all these projects.

Figure 1. Multiple projects hitting the product team, requiring them to coordinate with the other teams involved in the value stream

Figure 1. Multiple projects hitting the product team, requiring them to coordinate with the other teams involved in the value stream

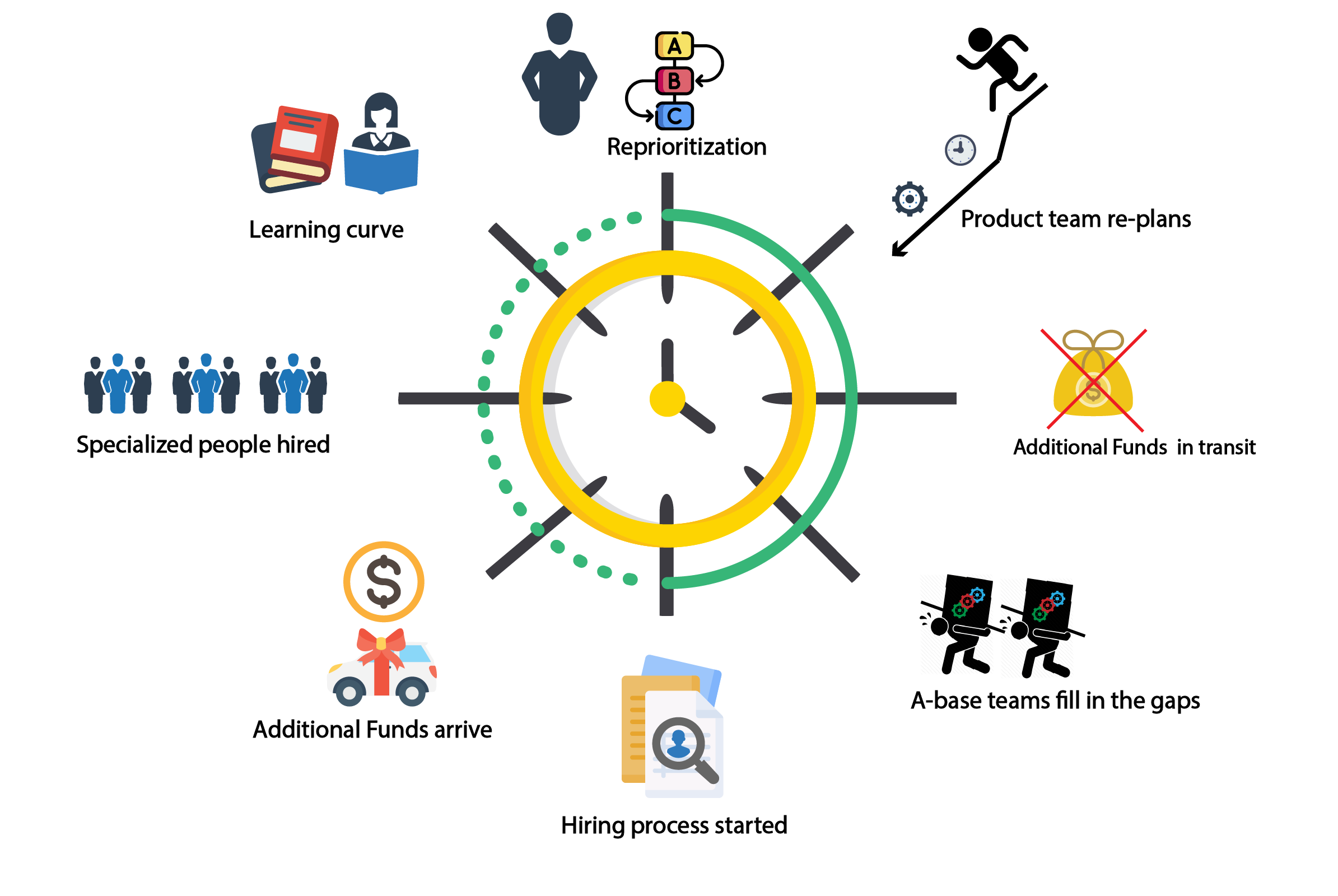

When re-prioritization at the organization level occurs, a large-scale shift in demands occurs. The limited internal capacity of the IT organization needs to be re-adjusted to follow this new set of priorities. This usually results in A-Base funding re-allocation to fulfill pre-made commitments to the new priority projects because the IT organization cannot wait for new funds to be released (funds from the programs funding these projects or released by TB subs). This leaves the IT organizations dipping into funds it currently has: either from existing program funding or with annual updates. The IT organization’s A-Base, funding its salary workforce meant to keep the lights on (operations), is then heavily involved in carrying the work until funding gets adjusted, HR processes for hiring new positions completes, and Procurement processes for acquiring services finishes.

Figure 2. Re-prioritization of projects will require A-Base funded teams to take the load until new project funds are made available to increase internal capacity

Figure 2. Re-prioritization of projects will require A-Base funded teams to take the load until new project funds are made available to increase internal capacity

Additionally, it’s worth noting that this advance planning effort is done using internal capacity and ends up partially wasted6. Doing extensive planning and design work that locks us into a rigidly defined feature set does not take advantage of the fact that software can be quickly and easily modified (if well architected) to incorporate new functionality that we didn’t even know about when we did the planning and scheduling several months prior. In addition, during the requirement gathering and scheduling steps, the IT teams will make many assumptions and estimates because every new IT project we do is unique7. Because of this, the teams have limited experience doing exactly what we ask them to do and, as a result, the actual implementation is filled with many discoveries and assumptions made up front that are later found to be incorrect when actual development begins.

Finally, it’s at implementation, in production, that end-users then discover, months after development began, whether we misunderstood what was wanted, that new conditions made a particular feature less important than others, or even if the feature is no longer useful.

Due to the habit of projectizing large investments, advance long-term planning is deemed required to package effort into a quantifiable bundle for senior management decision making. Decisions that expect costing and scheduling estimates to be included in these bundles.

The greater effects to the department

Project Management is an investment method meant to be used when there is high-certainty in a problem and high-agreement in a solution8. But if we are not sure about them, as is the case with moving towards digital where the definition of done is defined by the end-user, what investment instrument can we use?

A negative effect of locking ourselves into too long of a delivery delay is that 50% of all software is never used or does not meet its business objectives9. Even though business enhancements should first start with user research, until a feature is put in the hands of the user, we cannot be 100% sure that it’s valuable. In fact, a Microsoft research showed that only about 1/3 of well-designed, well-research features in mature products deliver top-line value to organizations10.

There are multiple sources highlighting the low success rates of large IT-Enabled projects9. This because we used to quantify “success” as being on time, on budget, and as per requirements. There has been significant progress these last few years in quantifying success towards “what this investment means to Canadians” (especially coming from our pandemic response successes). Authorities are now seeking assurances that a particular investment adds value. So then, how do we quantify value? And how do we give confidence to those authorities that we are not asking for a blank cheque?

Moving to a different software investment management method

Since we expect moving to Digital means business operations will be done with software, it warrants us to review how we fund software investments so to enable faster feedback loop between policy makers and end-users. This to meet the Government of Canada’s second Digital Standard: Iterate and improve frequently.

We are looking at different methods favouring planning around product roadmaps, with stable funding for value streams made up of multi-disciplinary team members that can sustain demands and make timely decisions reflecting end-user needs, and a governance that measures progress through working software instead of planning documents.

Product management ultimately accepts that, although we know the objectives to achieve, we can’t adequately predict end user behaviours. We require a broad set of skills working together in monitoring and continuously improving at a pace of the end-user needs. We must use public funds in a responsible way by navigating this uncertainty through smaller iterative steps, making course corrections using empirical evidence, and constantly providing value until the end user tells us our goal is achieved. We are looking to see if we can adjust our investment management instruments tool box, including how we submit TB Submissions, and release much needed internal IT capacity.

A subsequent blog will be posted to share our thoughts on the topic of product management and how we think it could be implemented in government.

Notes

-

IT-Enabled means a project with a technology component. The 103 number comes from a 2021-03-29 snapshot and includes projects with a status of approved (started or not started) or on hold ↩

-

There were 26 projects with sufficient data to measure the average time to start stage 4 ↩

-

Expenditure Approval means that the work proposed (packaged as a TB sub) aligns with parliamentary priorities and is part of the mechanism government can show accountability to a democratically elected parliament. See this excellent online course on the subject. ↩

-

Multiple books and research on the subject support this statement, including Team Topologies, Project to Product, Leading the Transformation – Applying Agile and DevOps at Scale, and the DevOps Research and Assessment (DORA) institute ↩

-

While small software applications may be managed by a single team, large scale ones require collaboration with other teams like IT Security, Data Professionals, Quality Assurance, Platform Team, Cloud Engineering, On premise System Administrators, and Architects. ↩

-

The authors of Leading the Transformation suggest software costs are driven to 20-30% higher because of this “waterfall” method ↩

-

Software is a creative process where every new problem to solve is different than the previous ones. A software project cannot simply be quantified in terms of number of lines of code, number of defects to fix, or number of requirements. If you’re an IT professional, you know this. If not, this is highlighted in the books and research Team Topologies, Project to Product, Leading the Transformation – Applying Agile and DevOps at Scale, and the DevOps Research and Assessment (DORA) institute ↩

-

What is Product Management in Government? By Scott Colfer, head of Product in UK government ↩

-

Ronny Kohavi et al, Online Experiments at Microsoft, 2009 ↩ ↩2

-

Ronny Kohavi et al, Online Experiments at Microsoft, 2009, section 5.1 ↩