Case for Continuous Improvement: A Deeper Dive

In my previous post, I have tried to use maths to prove that continuous improvement would provide greater value than the status quo to any organization were they to embed the practice in their way of working. In this post, I propose the reader a deeper dive and some potential improvements over this analysis.

Here we’re going to use a little math trickery with some basic integration (well, basic as far as integration goes, anyways) and some discussion about how one could use velocity or business value points (gilealliance.org/resources/sessions/business-value-estimation/) to refine what the ideal trade off would be.

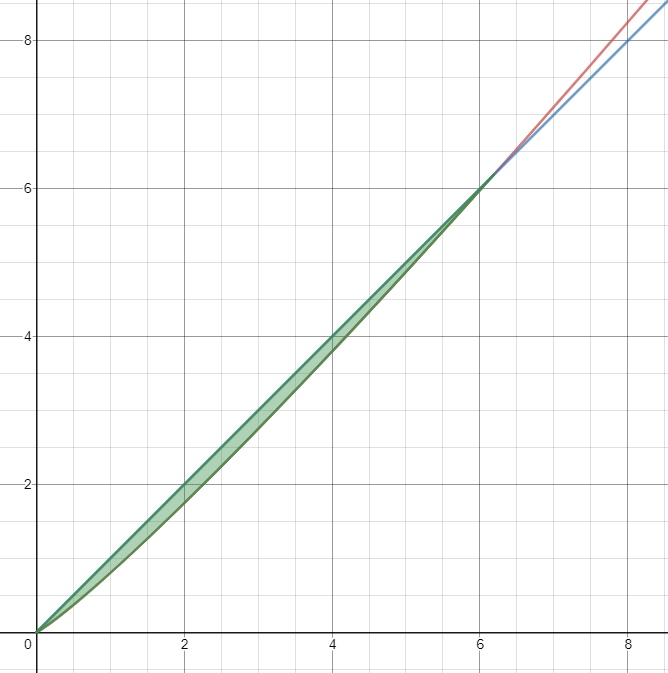

Step one here is to answer the question, “Well exactly how much time am I losing when I choose to invest in continuous learning?” Should I invest 20% of my time for a 10% trade off? Or would it be better to invest 30% of my time for a 20% trade off? To answer this question, we’ll need to learn more about the relationships between our two curves. More precisely, we need to know the area between the two curves. Luckily with desmos the heavy lifting is done for us. If you haven’t already done so, click here for an example. You should see something as follows

What are we seeing here? If you hover over where the two lines intercept, you will see that the x value is 6.192, which is the same 6.192 you will see in the integral

\[\begin{align*} \int_0^{6.192} f(x) \,dx=18.0750720063 \end{align*}\]Line 3 should read

f(x) <= y <= F(x)

And you should see that one line 1 and 2 we have defined f(x) and F(x), respectively, as we covered above. A small detail we glanced over before is the { x > 0 }, which is specifying to only draw the line where x > 0 (to prevent the lines from going past the x-axis which adds noise to our graph).

You will also notice that in our picture of the integral is displayed a number, ~18.075. This is the area under the curve f(x) between x=0 and x=6.192. Next we find the area under F(x) (which was equal x), which is (width x height) / 2 (the area of a triangle), which is ~19.17. Then, on line 8, we substract the integral from the triangle to find the area of the curve that is under F(x) which is not under f(x). In our case, this turns out to be

19.17 - 18.075 ~= 1.0953

In this case then, we can say that we have lost ~1.0953 units of productivity initially when we started working continuously, if we spend 20% of our time in order to increase our efficiency by 10%.

Why is this important? This represents the size of the difference between what you would have delivered had you not started to continuously improve. It can give us useful insights about how to play with r versus l to realize the greatest efficiency gains. For example, if we were to realize even greater efficiency gains for our 20% time investment, the area of the curve would decrease even more.

Click here for an example. Here we assume that for 20% time investment we realize a 20% efficiency gain. In this case the area of the space between the curves is reduced to ~0.3377

The relevant question for one here is, what is more important to your team? Being as productive as possible as quickly as possible, or is it acting in such a way that one is able to continually improve, though with the smallest possible impact on their clients and ability to produce.

In the Phoenix Project, the company stops all projects to focus on improving the way they work. Following this, they are able to deliver and meet all of their deadlines and successfully deliver the previously doomed project. How would we demonstrate that this is in fact the optimal approach to take? We already have the tools to do so above!

Option 1: It is more important to become as productive as possible, as quickly as possible

If this is your team, then you should opt for a situation where the team can maximize r as quickly as possible, even if it requires a higher-time investment. As x increases, the exponential curve will continue to grow faster and faster than the linear function. Therefore, it is more important to maximize r than it is to minimize l.

One may say, “well in that case, I could maximize r by setting l to 100%, in which case all one would do is spend time improving rather than delivering to their users or clients.” You could! And in the Phoenix Project that is what they do! Granted, one should only do this for a short period of time. In the future, we should elaborate on the function to account for the decline in productivity as t increases assuming an unsustainably high value of r. However, for a short period of time, if a team feels there are enough quick wins to be had to justify the increased productivity, they very well could invest 100% of their time towards self improvement for a brief period. Following this brief blitz the team should then find a sustainable value whereby they are able to continuously improve using l percentage of their time such that it would still result in a good ratio between l and r. That is, that the time invested is still increasing the value of r comparatively.

For example, when it comes to looking for a sustainable value of l and r, a team may iterate and adjust accordingly:

- I invest 10% of my time for a 10% increase in productivity, which results in what my team judges to be a good ratio (1:1).

- The team increases to 20% of their time for a 20% increase in productivity, making this a good decision to make (1:1).

- However, if I increase l to 40% of my time, and only see a 25% increase in r, then perhaps revising l down to the highest value of l for which I maintain the 1:1 ratio would be a better approach.

This is just an example and the situation will change depending on your team. If increasing r is important to your team, then perhaps a reduction in the ratio is acceptable to you to a certain point. Perhaps 4:2.5 (l = 40; r = 25) is worth it to your team, given that f(x) is exponential, the team that does choose to invest more in l will eventually be more productive than the team who opted for a 1:1 ratio.

See here for an example. In this abstract case, we can see that the team who opted for the 4:2.5 ratio will end up being more productive than the 1:1 team after ~10.572 months.

It is important to remember our previous discussion about the decay of r as a team over invests in l, however.

Option 2: Begin to continuously improve while still meeting the current expectations as best as possible.

The Intuitive Option: Minimize l such that a small percentage of our time is dedicated to continuous learning so that we can continue to deliver on our responsibilities.

The Better Option: Pick the lowest value of l such that it maximizes the value of r

Let’s do an example.

If we set l = 30% and r = 20%, then we will find the area between the curves, that is the total initial lost productivity, is ~0.8146 (confirm here)

Perhaps this loss in efficiency is unacceptable to an operations team. What is to be done then?

What we recommend is identifying quick wins. Find the set of tasks that given the smallest amount of time invested, l, will realize the greatest efficiency gains.

If 30% of time dedicated to continuous improvement is too high though we know a few common pain points that would greatly simplify the lives of the team members, perhaps for investing 10% of our time we could still realize 15% rate of improvement. In this case, if we plug these numbers into our functions (as we have done here), you will find that our new area between the curves is ~0.1367. By reducing the value of l we have reduced the area between the curves (productivity lost), while maximizing the value of r, which, due to the relationship between exponential and linear functions, is our priority.

This quick win trade off is a short term game, however, as you cannot expect that ratio between l:r to continue at that rate forever. Once your team has stopped working at 120% through quick wins, it is time to settle into a constant rate of continuous improvement for your team. As we covered above, around 20% is likely the lowest you would want to go. The key is to find a value that is sustainable for your team, as the real magic we are trying to leverage is the power of the continuous or compounding improvement, so that we benefit from exponential efficiency gains.

In conclusion, if one is looking for maximum productivity it is best to maximize the value of r, and if one is looking to minimize the impact to their current services one should find the lowest value of l such that it maximizes the possible value for r.

The next question to be answered then would be how one would find what their r is given some investment l. To do this, one needs metrics.

One possible option that comes to mind is the use of velocity and business value. Velocity alone will not suffice, as given the same amount of effort by the team they should become more productive. Therefore, while velocity remains constant (or, rather, the team’s average velocity stays consistent) the amount of business value delivered should increase. Therefore, one can measure the rate of increased productivity r by computing the rate of increase between the velocity and the business value. Each sprint then, a team could calculate

i = business value/velocity

which will give you the amount of business value produced per unit of effort required. Week after week as you compute this value, compute the rate of change of i. This will, over time, give you the rate at which you are improving over some interval of time.

Granted, this is assuming no significant changes in the team, and that humans, given changing circumstances, continue to give consistent evaluations throughout the process. It’s not perfect I admit, and if anyone else has any more rigorous ways by which to define r, we’d love to hear from you and please submit an issue here.

In this section I have attempted to add some rigours by which we can better measure what the best approach would be for a team given their goals. More time should be spent determining the best possible way to define r.

Future Improvements

This section here acknowledges some of the points I’d like to improve, though if you would like to contribute here are to particular issues I need to revisit later.

Problem 1: Desmos syntax

On desmos I couldn’t figure out how to store the x coordinate of where the lines intercepted to store the variable in maximum value for the integral.

Problem 2: Loss on ROI as time spent increases

Given the function

f(x) = x1+r - x*l

As x grows there should be some function by which the exponent 1+r begins to reduce, as the quick wins are solved it will gradually take more effort to realize the same amount of efficiency.

Problem 3: Anything you can think of or anything that was missed

If you found that we have made any mistakes in the article above or if you have recommendations to improve it, we’d love to hear from you to learn how we can improve it and make it better! Please open an issue here. We’re always looking to continue learning and improve our content!

The End

Thanks for reading! My previous blog post was my attempt at going from simple to more complex in an attempt to try and more formally and rigorously define the logic behind committing to continually improving. This second post was intended for the more committed reader to try and more deeply explore the outputs desired from continually improving, and what we should take into consideration when doing so. This blog post was a blast to write. I love applying the rigour math can offer to the real world, so the last section is a call-out to fellow enthusiasts who would enjoy helping me dig deeper into such topics.

Thanks for reading!

Edited on 2020-01-01: The post was edited to add the main author.