Pilot IITB Guidance on Product Management

DISCLAIMER

This document does NOT attempt to explain all aspects of Product Management (such as vision setting, user research, and the different phases a product goes through in its life cycle). These are well documented already, such as on PMI.org and PDMA.org.

Instead, this documents seeks to provide structure to ESDC Programs and IITB in the transition from project to product, within a Canadian federal government context. In particular, the rationale and methods to cross-functional and cross-branch product teams.

Table of Content

- Introduction

- Narrative

- Guidance on Specific Directive Elements

- Governance

- Role of Enterprise Architecture in Relation to Product Management

- Phase 2 of the IITB Way Forward

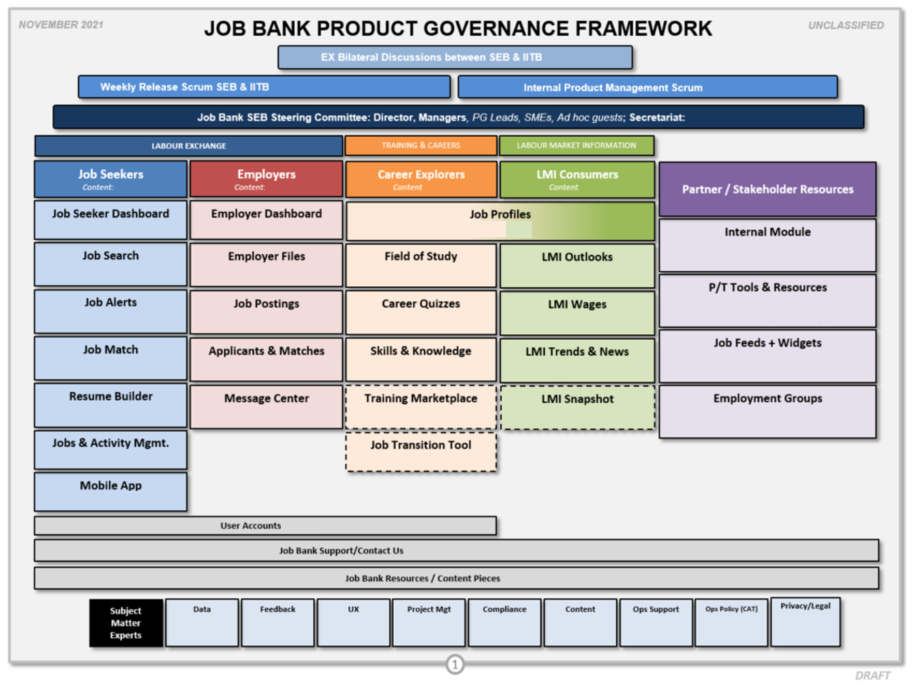

- Appendix A - Business View of Job Bank’s Family of Products

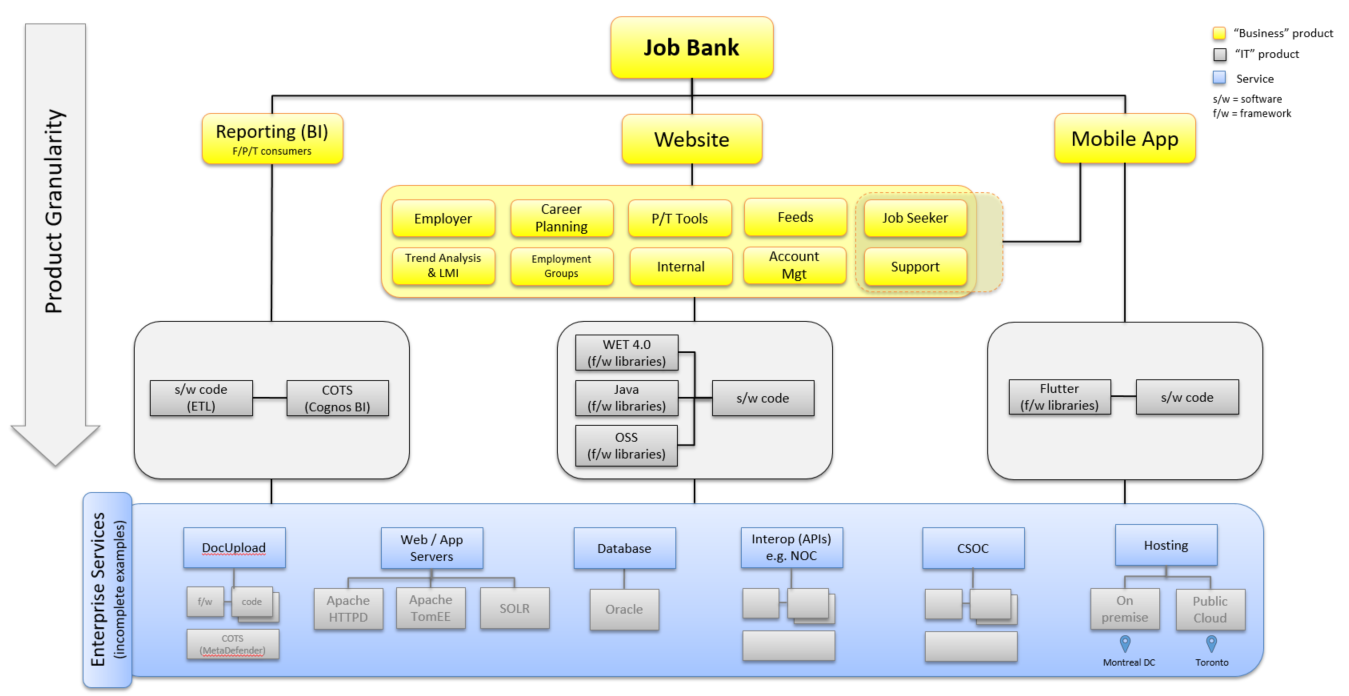

- Appendix B - IT View of Job Bank’s Family of Products of Products

- Appendix C - Definitions

Introduction

Document Purpose

To provide guidance in implementing the Pilot IITB Directive on Product Management and its associated Standards.

The Directive, Standard, and Procedures strive to be succinct. Any context, explications, and situational awareness for the reader has been moved to this document.

References

This document provides guidance on the following documents:

- Pilot IITB Directive on Product Management

- Pilot IITB Standards on Product Management

- Pilot IITB Procedures on Product Management

Enquiries

Please direct enquiries about this Pilot directive to the IITB IT Strategy team.

Narrative

This section provides context and describes the causal relationship between the elements of the Directive (rules to follow), its associated Standard (more detailed rules such as formats and specific information required), and their expected outcomes. Job Bank is used as an example.

Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) provides multiples services via its 50 Programs to improve the standard of living and quality of life for all Canadians. One of those Programs is Job Bank.

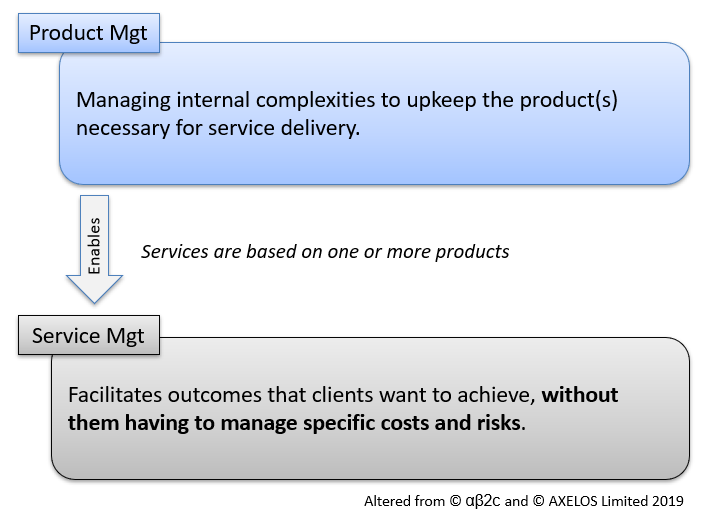

Products can be tied to Service delivery, then to Programs the following way.

A service leverages products for its delivery. Managing the internal complexities to sustain these products AND how they affect the service level is where product management fits. Moving to digital means some of those products will be exposed to service consumer (e.g. a website).

The words “Job Bank” can actually be understood to mean three separate things:

- It’s a Program

- It’s a free Service to job seekers and employers, ultimately measured using the Program’s Performance Information Profile (PIP)

- And it’s a family of products, most notably ten of them making up its website exposed and consumed by clients as part of Job Bank’s service delivery (See Appendix A and Appendix B).

Interactions with the website has a direct impact on the Service performance AND gives rapid insights for improvements as interactions with software generates large amount of data. This is the new opportunity that Digital brings: the ability to quickly act on those insights, using evidence-based decision making. All with the objective to improve the results that Programs are being evaluated against via the TB Policy on Results. For example, Job Bank’s results being displayed in GC’s InfoBase.

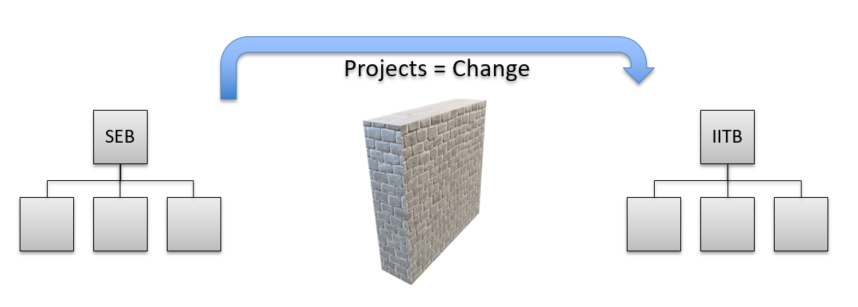

In the traditional Program-Corporate relationship, IT gets funding to “keep the lights on” and projects are used when Programs want to engage IT staff to make software changes. This can create unnecessary lag for much needed small improvements.

In an ideal digital world a departmental product “team”, like Job Bank, should embed both business and IT staff. However, because Treasury Board Policies regulating Programs and Corporate put different persons in charge of IT and Program functions, these two separate persons will naturally want the staff responsible for their function in their respective org charts.

This is where we want to differentiate improvements from projects and enable funding teams with cross-branch memberships.

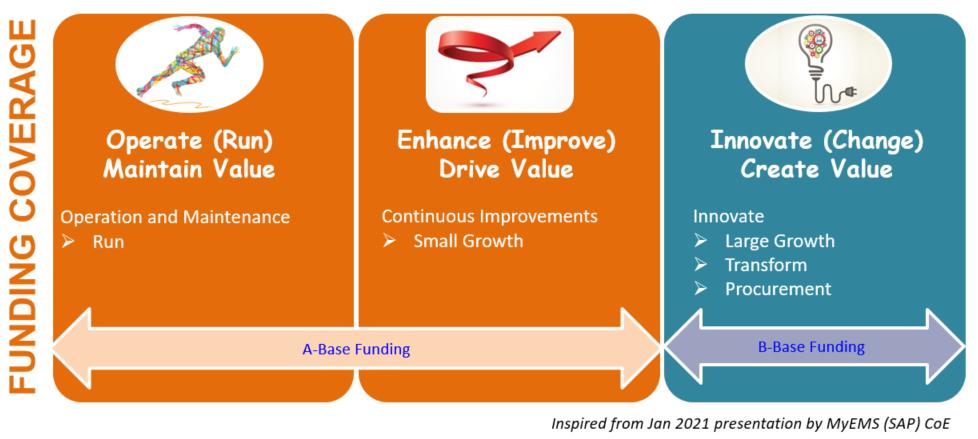

Funding for RUN activities continues to be used for “keeping the lights on”.

Projects are used to coordinate large change, such as changing the enterprise through a transformation or needing to coordinate change over multiple products.

In between however, there is an opportunity to allow rapid, small, changes to software: enabling continuous improvements. Typically on existing business processes, to enhance user experience, and continuously address cyber security risks.

A few things are necessary to enable such continuous improvements, which is the focus of the Directive and Standard.

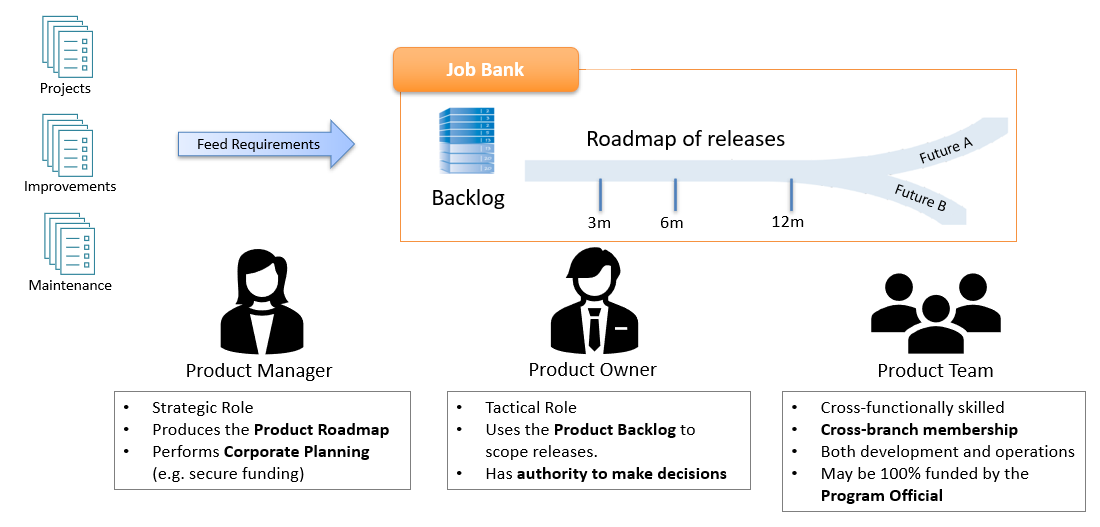

The different kinds of work affecting a particular product are requirements feeding that product’s backlog. Product Teams perform their own improvements and maintenance activities, while external Projects bring work to them.

To manage and coordinate all this demand, Product Managers are used. As a strategic role they look beyond a 6 month time horizon. Product Managers use the product’s roadmap as both a communication tool AND a negotiating one. Collaborating with the different project managers on what is reasonable to do over a time horizon. A Product Manager also ensures the product team is well equipped to handle demands, such as performing financial, HR, and Architectural planning (e.g. securing funding).

Product Owners are a more tactical role. They look within a 6 month time horizon. They work closely with Product Managers and the product roadmap to scope releases and have ultimate authority to make decisions on the product. A Product Owner works with the product team to elaborate more detailed requirements from the roadmap’s high level ones, and may engage other IT professionals when need be (e.g. IT Security).

In a cross-branch product team sponsored by a Branch, both the product manager and the product owner sits on the Program side. Though it is expected they will have to work closely with IT Managers to fully understand the implications of risks, such as creeping technical debt and cyber security, has on their product’s livelihood as well as ensuring compliance to IM/IT Policies (e.g. IT Security’s software patching requirements).

Breaking down the main product that is Job Bank into its 10 “business product”, we expect such large Product to require a “Head of Product” overseeing all sub-products. In addition, those 10 Job Bank “business product” would each have a Product Manager and Owner assigned that sits on the Program side. Those 10 products are further broken down into their IT elements (e.g. software code and libraries hosted on servers or in the public cloud). These more granular “internal IT products” may also be assigned Product Managers and Owners but would more realistically sit on the IT side.

The Product Team is made up of cross-functionally skilled members, from multiple branches. This is the space where Agile and DevSecOps fit in. The faster pace of release necessary to avoid clogging delivery promotes their adoption. Product teams must be well trained in Agile, otherwise chaos can creep in and negatively affect their performance, or worst, communicate to senior management that “Agile doesn’t work”.

Other roles are necessary, such as the IT Security Champion one. This is because the pace of change expected and the risks associated to even small software changes warrants security expertise to be embedded in the product team. This further promotes equipping product teams with the right tools and even warrants delegating certain architectural decisions to product teams as they are the ones suffering the consequences of some technology choice(s).

Funding of cross-branch product team is expected to be as such:

- The Program Official budgets and identifies his source of funds for IT work. For Job Bank, as an example, the source would be the Canadian Employment Insurance Commission. So in its periodic Treasury Board submission renewals, Job Bank needs to identify sufficient funding not just for its Program staff, but also for IT work.

- Once IT funding is secured as part of a TB submission, it is transferred to IITB and used to fund dedicated IT staff for that Program (staff that will remain in IITB).

- A Memorandum of Understanding (MOUs) between the CIO and the Program Official is used to solidify this arrangements.

We expect conditions over those funds as a means to provide Corporate (the CFO and the CIO) with sufficient assurance in the use of public funds and the responsibilities coming with software.

We also do not expect EARB and ARC to be involved in approving or endorsing such funding. This because EARB and ARC are focused on the enterprise and improving an existing product has negligible effects on the enterprise. EARB and ARC is involved in Projects.

These conditions and the trust level provided to product teams can be managed through a Directive’s consequences of non-compliance. Such as, if non-compliant, adding layers of governance during the product team’s yearly funding cycle.

It’s worth noting that projectization is still needed to coordinate work across product teams and to bring workload to them.

To increase a product team’s capacity, existing funding pressure instruments are used. E.g. if a $2M/year product team can’t meet demand for a given year, departmental funding pressure can be used to increase it to $4M/year. For a cross-branch product team funded by a Program Official, this funding pressure should be done on the Program Official’s branch.

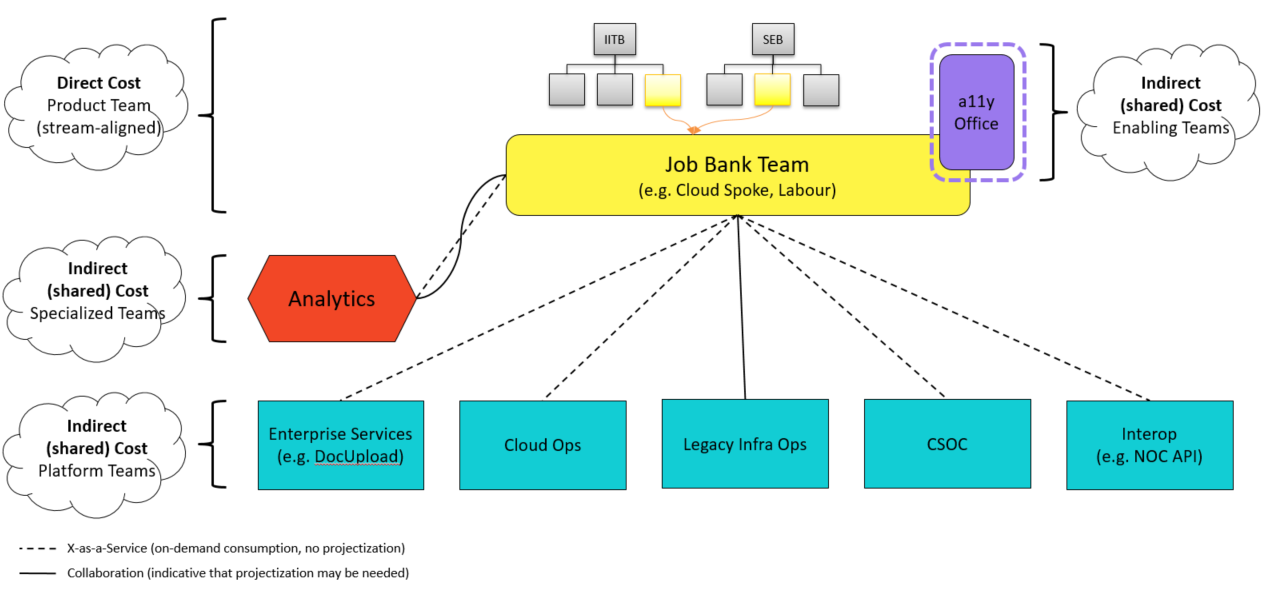

This dedicated cross-branch product team can still interact with other IITB teams. To explain this interaction, we use team topologies concepts.

There are four types of teams that interact. The “stream-aligned” team is what the Program Official is funding to create, for example, the Job Bank team. Its cloud credit (if using public cloud services) and labour costs can be directly attributed to the Program.

The other three types of teams cannot be directly attributed to a single Program, their costs are essentially shared. Making up the “IT Corporate Services” space. Their funding and sustainability requires pooling funds into the CIO budget. Unless they can provide on-demand services, via APIs, their engagements may need to be projectized as stream-aligned teams would essentially be competing for their time commitments.

Specialized teams provide significant expertise in some areas when need be. For example, relational database performance, advance data modeling, mathematics and calculations. These teams are typically first engaged as part of projects, then continue by providing services. E.g. setting up a Business Intelligence (BI) COTS product for the stream-aligned team then letting the stream-aligned team manage the BI’s reports.

Enabling teams help other teams overcome obstacles. They coach and mentor them until they’ve gained sufficient expertise, at which point they step away. Enabling teams are essentially temporary in nature.

Platform teams provide compelling internal products and services to accelerate delivery by stream-aligned teams. One example for Job Bank is that it uses a DocUpload service that allows clients to upload documents, then performs anti-virus scans, and stores them securely. Re-using such service enables the organizations to save time and money.

Guidance on Specific Directive Elements

Product Team Setup

A new product is expected to be created after an investment project. Therefore, the transition from project to product should start no later than in the project’s closing stage (stage 5), preferably before hand so to give sufficient time for formalities to be established. See ESDC’s Directive on Project Management for reference.

This transition requires the Program Official (or a senior level official in an ESDC Branch) to find sufficient funding to sustain not only the “run” operations (i.e. maintenance work on the product), but also small and continuous improvements. The budget for such improvement includes both business and IT work. Estimating the budget should be informed by the following:

- Number of small software releases estimated to be performed each year. Small releases are typically for maintenance, bug fixes, and cyber security risk mitigation.

- Number of medium software releases estimated to be performed each year. Medium releases are typically for new product features that need a level of change management being performed and scoped within the product.

- Number of large software releases estimated to be performed each year. Drivers for large releases should come from outside projects impacting the product, such as legislation changes and transformational agenda.

Such funding may be obtained via an agreement with the CIO in using the CIO’s budget, but is preferred to come directly from the Program funding source(s). Funding sources from the Program will require to add IT expenditure cost in the Program’s Treasury Board submission renewal using the estimated yearly budget mentioned above.

It is expected that such funding will require the Program Official to produce a compelling business case. It is recommended to anchor the business case in:

- The Program’s Performance Information Profile’s expected outcomes,

- ESDC’s Digital Service Transformation objectives

- Situating the Program’s services (that the product team fits in) in ESDC’s Service Target Operating Model

- A Branch’s Assistant Deputy Minister’s articulated goal(s)

The Business Architecture team may be used to provide advice.

It is NOT needed to go through EARB or ARC for endorsements. EARB and ARC will have been involved in projects bringing work to your product before they reach your backlog.

The above refers to the following Directive’s requirements:

- The Product Team’s yearly budget includes both IITB and Program area work

- The Product Team has source(s) of funds identified and secured

- Funds for the Product Team’s IT work are transferred to IITB on a yearly basis

Corporate will want to have a view of how the product team is governed and structured to get assurance that a level of discipline is used by the product team to make decisions. Hence why documentation of the product team’s governance and cross-organizational chart are requirements.

This arrangement between the Program area and the CIO in fund transfers and dedicated IT staff is to be formalized under a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), identifying to which Program and/or Corporate Functions this arrangement is being tied to.

Should funding pressures be needed to increase a product team’s capacity, those pressures are put on the Sponsoring Branch (not IITB).

The location of the different repositories that the product uses to store its requirements needs to be known as projects seeking to bring workload to the product team will need to know where to add them. Hence why documenting and making available the product team’s requirements repository(ies).

IITB, as part of the Directive on Service and Digital integrated planning requirements, need to document which applications from the APM Inventory is being worked on. The APM inventory, known internally in IITB as the “Corporate Solutions Directory”, has a different representation of “products” than Programs do. This is fine, it’s the “IT view” of things. Hence why the requirement to identify the applications from the APM Inventory.

Finally, all this information is asked to be documented in a place for easy access by Corporate and external project teams.

Roles and Responsibilities

Different Corporate authorities are responsible to assure sound stewardship of public funds and the management of IM and IT. In investment projects, this assurance is done through gating process where project teams demonstrate they have done sufficient due diligence by producing certain project artefacts (e.g. outputs of analysis and formalizing agreements amongst stakeholders).

Because some work between the cross-branch product team will not be projectized, and so will not require to be brought to those Corporate authorities, some level of assurance is needed that those responsibilities are still being upheld.

It is expected that a product team will need to have high maturity in project management, Agile methodologies, and product management. This IITB Directive strives to provide as much flexibility to product teams on how they will organize internally by not prescribing any methodologies. Whether it be SCRUM, Kanban, or more traditional business-functional-technical specification, it does not matter to Corporate oversight. However, certain roles and their associated responsibilities are still expected regardless of which methodology is used.

Section 5.2 of the IITB Directive lists the different roles that must be assigned to members of the product teams.

Depending on the scale of the product, a single person may fulfill more than one role. That person is still identified for each role so that external teams (such as project team) know who to contact for a particular topic.

Although the roles of Head of Product, Product Manager, and Product Owner is expected to sit on the Program side, their activities are expected to heavily involve IT managers. The Product’s strategy, roadmap, and scope of releases all require being informed with IT considerations so to remain realistic, achievable, and sustainable (e.g. timely remediation of technical debt).

A Head of Product is believed to be executive level due to the oversight and responsibilities expected of it, though it is not a requirement to be one.

Sources used to define the responsibilities of roles are as follows:

- Product Manager: from Product Development and Management Association’s Body of Knowledge second edition, from 280group, GOV.uk’s guidance.

- Product Owner: from Info-Tech Research Group and Gartner

- IT Security Champion: from SLF’s January 2021 presentation (modified last point)

- Change Coordinator: from Info-Tech Research Group

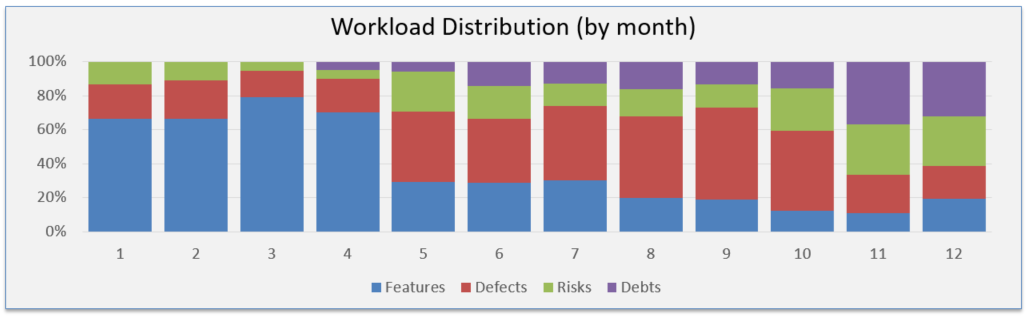

An optional dashboard for Product Managers and Owners to use in order to help quantify the types of work being managed, and so help with IT Manager communications, is the monthly workload distribution dashboard.

In this dashboard, there are four types of work:

- Features: Seen by end users. A new functionality or ability.

- Defects: Seen by end users. A broken functionality or ability.

- Risks: NOT seen by end users. A compliance gap (e.g. cyber security).

- Debts: NOT seen by end users. A technical, process, or people debt needing to address to improve throughput (e.g. architecture refactoring, new API, investment in automation).

Oversight and Reporting

Oversight and reporting provide Corporate authorities with some evidence that public funds are being spent on outcomes and that the product team “knows what it’s doing”. Striving to provide as much autonomy as possible to product teams while upholding the responsibilities mentioned above, a minimum of four artifacts are expected to be produced and, if being asked, provided to Corporate Authorities:

- The Product’s Roadmap. The Product Team may use more than one “view” of the product roadmap’s for its internal coordination and communication. For this Directive, Corporate will seek to have an executive level view of the milestones and outcomes expected to be obtained over a fiscal year.

- Release Retrospectives. Product Management seeks to continuously improve using evidence-based decision making. Every change release of a product needs to be evaluated against the desired outcomes that were sought in that release and analyzed on their successful or negative results. The timing of such retrospectives is left at the discretion of the product team (e.g. do retrospectives 2 months after a release so to give sufficient time for data to be generated).

- Software Delivery Performance Metrics. The DevOps Research and Assessment (DORA) Institute, now bought by Google, researched the four key metrics that define high performing technology organizations. In addition to the above retrospectives on business outcomes, the product team should strive to continuously improve its software delivery capabilities. These DORA metrics are meant to show Corporate that the product team is making improvements in that regards and takes serious consideration on the effects that creeping technical debt, quality, and cyber security has on the health of their product(s).

- A Risk Register. Same as in project management, Corporate authorities needs to be assured that the product team understands the risks that change can have on their product and the organization. It is expected that product team will be disciplined in identifying risks to their operations and know how to handle them. A typical source of risk is the “Threats” identify after performing SWOT analyses. The ESDC Guide to Risk Management may be leveraged.

- Endorsement of the Product Roadmap. In order to ensure that the product team accounts for IT’s interests, which affects the CIO’s accountability such as software patching, technical debt remediation, and cyber security risks, the Head of Product is asked to have their Product Roadmap endorsed at PPRC as part of the product team’s yearly funding cycle.

Consequences of Non-Compliance

Consequences of non-compliance are used to motivate product teams to maintain a high level of integrity and performance necessary to retain the level of autonomy provided by the Directive.

Governance authorities may, on occasion, request certain evidence from the project team that they are behaving according to the Directive. These may be in the form of an audit or an invitation to a corporate committee (e.g. invited to DGPOC in presenting their product’s roadmap and a summary of their recent retrospectives).

Failure to comply with the Directive and associated Standard requirements will result consequences of gradual severity.

As such, consequences vary from notification, to training, to adding layers of governance in a team’s yearly funding cycle, up to cancelling the agreement between IITB and the sponsoring Branch’s ADM

As expertise in Agile methods and DevSecOps are expected to be required, IITB is investing in maturity assessment tooling and training, such as:

- Maturity Assessment using IITB’s SDLC & Product Delivery Guidebook

- Agile Training (e.g. using the Interoperability team’s services)

- Product Management Training (e.g. using external firm services)

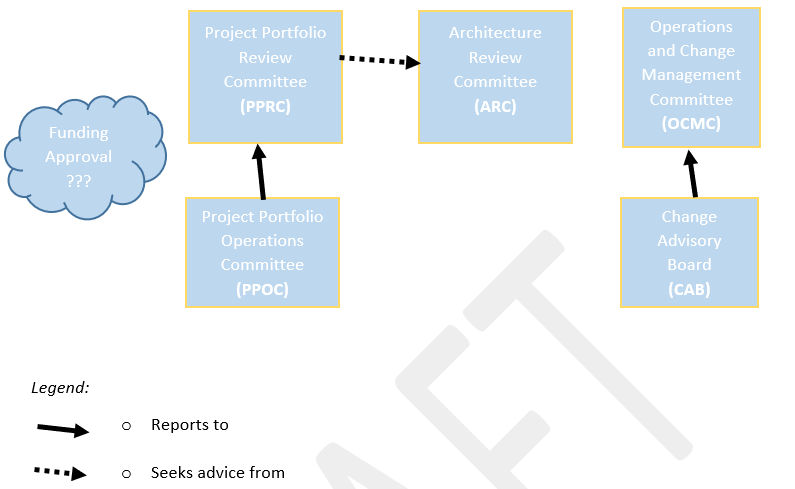

Governance

This section helps situate product teams work within the greater corporate governance landscape.

The pilot product management framework leverages existing governance bodies (e.g. PPRC) and instruments (e.g. release management), it does not replace them.

Governance Overview

| Governance Body | Role within Product Management |

|---|---|

| PPRC | Oversees the spending of IT-related funds and approves the yearly product roadmap. May seek recommendations from ARC on product roadmap-related outcomes. |

| PPOC | Tracks spending of IT funds towards the product roadmap. Tracks non-compliances incident. Reports information to PPRC |

| ARC | Provides advice and recommendations to PPRC on alignment of the product roadmap’s to the departmental direction and standards |

| CAB | Provides advice and recommendations to PPRC on alignment of the product roadmap’s to the departmental direction and standards. Oversees changes to the IT infrastructure. Establishes the release management process that product teams are to use. |

| ??? | Approves the multi-year funding envelop for a product team. Funding that will be for both operational activities (e.g. support and maintenance) as well as some “grow” type activities (e.g. improvements). |

Outcome-Based Funding of Multi-Disciplinary Product Teams

The approach to fund multi-disciplinary teams leverages existing ESDC corporate instruments, such as investment projects and funding pressures, and seeks to capitalize on the benefits of loose coupling architectures (see next section on the role of Enterprise Architecture).

The goals of this approach are as follows:

- Position the funding responsibility on the Sponsoring Branch (not IITB)

- Leverage existing fund pressure instruments to increase product team capacity

- Establish dedicated IT personnel for a Sponsoring Branch

Funding of product teams come in two methods, both of which use outcomes to justify funding:

- As part of the base funding envelop provided at the team’s creation

- As part of funding pressures due to increase in demands for the product team (typically coming from investment projects)

The base funding envelop is set as part of the MOU between IITB and the Sponsoring Branch.

A new multi-disciplinary team will be created as part of an investment project. This because the justification for their existence requires a product to be created (see definition of “product” in the Directive and the guidance above on the use of projects in product management). It is the responsibility of the investment project to accurately determine the size of the team that will not only operate the product but perform continuous improvements on it over the years. As per the Directive’s requirement, key information for the creation of the product team is:

- Secured sources of funds that will be used to sustain its costs over the years

- A complete budget (both business and IT costs)

- The Sponsoring Branch

As part of this transition from project team to product team, the amount of IT personnel to make members of the new product team to fund will be identified. The Sponsoring Branch will transfer the funds necessary to support IT personnel to IITB. IITB will hire the IT personnel.

When new demands is brought to the product team (such as from non-gated projects, or from investment projects), the team’s Product Manager assess whether sufficient capacity exists for the team to supply that demand. Should capacity needs increasing, the funding pressure, even for IT work, is placed on the Sponsoring Branch. The Sponsoring Branch will negotiate with its financial advisors on options to available to it (such as negotiating with the Investment Project Sponsor to use their approved sources of funds).

The Sponsoring Branch also performs its prioritization of demands on their Sponsored multi-disciplinary product teams. For example, if the Sponsoring Branch only has a $4M budget to sustain two multi-disciplinary product teams and cannot increase its capacity, it will need to decide on which priorities can its two sponsored teams can focus on.

When Projects Are Used

Projects1 are used as part of product management. This section will provide guidance on when “formal projects” are used and their purpose (i.e. work formalized at corporate committees for oversight, such as investment projects and non-gated projects like Lite Projets).

Investment Projects are a response to a policy objective. They provide the necessary oversight for sound stewardship of public funds, ensure success focused on benefits, and alignment to departmental and government level priorities. As such, Investment Projects are expected to adjust ESDC products visions and roadmaps to align to such priorities, and are most likely the instigator of new products and their associated teams.

Investment Projects are governed by DGPOC and MPIB which grants permissions to use funds (contrary to popular belief DGPOC and MPIB does not give money). Investment Projects are therefore instruments that product teams can use to increase their capacity when demands surpass their ability to supply it. Project Sponsors should therefore involve Product Managers early on in the project planning phase to negotiate with them how their permissions to use funds can be used to meet project objectives.

Non-Gated projects such as the Lite Project may be used to coordinate work across product teams and compete for prioritization of work. These are expected to be leveraged when work requires the coordination with members outside of the product team. When a product team requires the involvement of another team (e.g. Job Bank product team requires the involvement of the Data Analytics Services team), this triggers two things:

- Increase in demand for the DAS team, prompting them to do funding pressures should they not be able to supply this demand

- Prioritization of work for the DAS team, that is which of their demands from their backlog must they accomplish at a given time.

Both these triggers leverage projects since funding pressure and portfolio prioritization decisions require projects.

Role of Enterprise Architecture in Relation to Product Management

This section does not attempt to describe what Enterprise Architecture is. This section focuses on how Enterprise Architecture and product teams benefit from each other.

Both the Enterprise Architecture function and the product teams provide insights to each other and so personnel in both areas must work closely together.

Organizational-level business and technology roadmaps

Enterprise architecture provides the organization-level business and technology roadmaps to product management which is an input into evolving the vision and roadmaps for a given product, identifying new potential features, and aligning to the greater departmental-level direction.

This information produced by the Enterprise Architecture function acts as input to the product team by:

- Supporting a product’s purpose, in relation to the departmental mandate and Program objectives

- Informing a product’s ever changing roadmap in terms of new features and compliance gap remediation

- Justifying investment decisions into the product

Product teams also provide inputs to the Enterprise Architecture function by providing their product roadmaps to inform evolving enterprise architecture in relation to:

- Emerging technological standards (product teams have a level of autonomy to acquire new technical stacks as long as it doesn’t increase its cognitive load and conforms with IM/IT security and accessibility policies).

- Limitations of current technology standards (e.g. explanations why certain standards are limiting product team performance or their ability to conform with policies).

- Capability gaps that the enterprise may want to invest in in order to reduce cognitive load to product teams (e.g. investing in a common service)

Architecture services

Enterprise Architecture provide services to product teams to share insights and expert advice. Such services are expected to be sought by the Product Manager and the IT Manager when informing their product roadmap. Example of services include:

- Providing expert advice on specialized topics (e.g. chatbots, public cloud architectures, migration pathways, new policies that the product team may not be aware of)

- Identifying opportunities for re-use (e.g. a new common service available to product team via an API)

- Mitigating organizational risks (e.g. cyber security, privacy, ethics)

- Ensuring quality and consistency of architectural artefacts making it easier to share information and move between teams.

Socialtechnical Architectures

Enterprise Architecture is involved in Projects, which act as responses to policy objectives. When projects require creating new or modifying existing digital solutions (that is, solutions that leverage software), Enterprise Architecture acts to ensure digital solutions are architected not only to align to departmental directions, but also to enable product teams to focus on value creation and provide them with the autonomy they seek.

The industry trend is to refer to this as socialtechnical architectures.

When digital solutions are built from loosely coupled, highly cohesive components it is easier to spread work across smaller teams. This reduces overall risk and organizational complexity, which in turn reduces time-to-delivery and enables teams to more quickly address cyber security vulnerabilities. The following cell-based reference architecture from WSO2 Inc. explains adapting Enterprise Architecture to capitalize on this opportunity.

Enterprise Architecture works on behalf of product teams to ensure departmental investments will benefit the personnel that will operate the solutions.

Common platforms to reduce cognitive loads and accelerate service delivery

Enterprise Architecture directs the organization to invest in common platforms as a means to not only save costs but also reduce cognitive load to product teams.

Common infrastructure enables continuous delivery by value streams. When there is a common technical infrastructure to delivery teams to deploy into it is easier to deploy. The easier it is to deploy, the more often it makes sense to deploy.

Application Portfolio Management (APM)

The APM function within Enterprise Architecture acts as a business intelligence by providing the organization with health indicators of its application portfolios.

As Products involves one or more applications from the APM inventory (e.g. Job Bank involves two main ones), Product Teams are required to keep their APM inventory up to date.

The Enterprise Architecture function leverages the APM information to map the organization application capabilities (e.g. how the “Identity and Access Management” application capability is being used by a particular Product Team).

The Business Architecture side of the Enterprise Architecture spans wider than the Product Team’s scope. As Products are used to enable certain business capabilities, it is expected that the mapping of a given product to a particular Business Capability will occur as part of a Project. Improvements of an existing product is unlikely to involve creating new or competing with existing business capabilities due to the limited funding envelop that a product team will have, and with PPRC’s oversight of the investment.

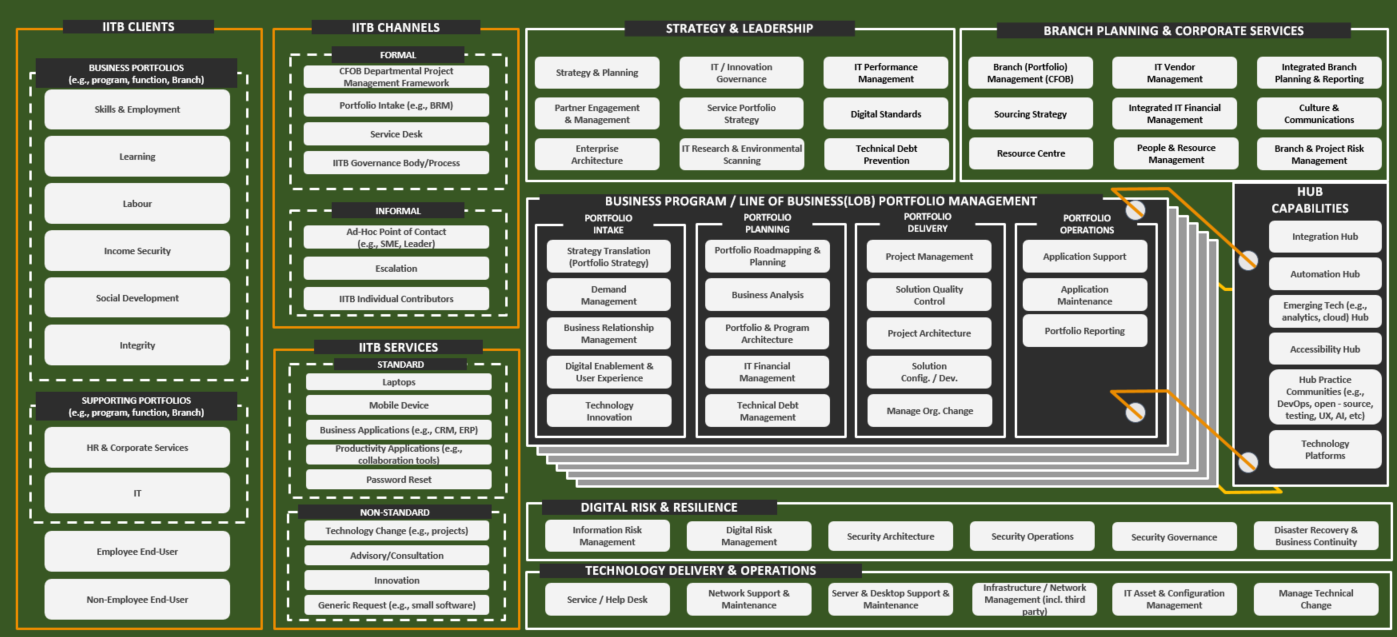

Phase 2 of the IITB Way Forward

In 2021, IITB re-organized itself as part of the Phase 2 of its IITB Way Forward plan. This re-org was informed from a 2020 independent study, mandated by the CIO and conducted by the PricewaterhouseCoopers firm.

The re-org is based on a product management model that follows a portfolio centric delivery environment supported by common services.

The intent of this pilot framework in providing sustainable funding to product teams for certain continuous improvement activities, and the guidance provided using team topologies concepts, aligns to the IITB Way Forward plan.

Appendix A - Business View of Job Bank’s Family of Products

Appendix B - IT View of Job Bank’s Family of Products of Products

Appendix C - Definitions

Projects: is defined by the Treasury Board as “an activity or series of activities that has a beginning and an end. A project is required to produce defined outputs and realize specific outcomes in support of a public policy objective, within a clear schedule and resource plan. A project is undertaken within specific time, cost, and performance parameters.” (source: PPPM)

Investment Projects: As per the ESDC Policy on Project and Programme Management, section 8.2, these are the “gated projects” used by ESDC with oversight at either DGPOC or MPIB.

Non-Gated projects: Lite Projects (for IT-enabled projects with oversight at PPOC) and Branch Initiatives (for non IT-enabled projects with oversight in Branch’s own governance).

-

See Appendix C on official definitions and the different kinds of projects that exist ↩