Team Topologies Inspired Whitelist App Development

A summary of the ideas and concepts used by the IT Strategy team and the DTS (Digital Technology Solutions) team to deliver the Whitelist application using DevOps inspired principles and ideas. By using this model, the team was able to demo an application to the CIO within 10 days of starting work, and had users testing the application within 2 hours of Protected B cloud becoming available.

Context

During the COVID-19 situation there was an urgent need for an application to assist with the management of important information regarding the internal use of human resources within the department. An application based on an open source project called Odoo was built to avoid compiling an unmanageable list of spreadsheets with inconsistent data. The IT Strategy Team alongside DTS worked to create a solution using modern approaches and methodologies, which are described below. By using the below model, the team was informally formed on a Thursday late afternoon and was able to begin demoing the application to users the following Monday – four days later (having worked through the weekend). By Tuesday, five days after the work began, the team had several repositories worth of work. An automated deployment pipeline was created in order to deploy changes to a development environment. Staging and production environments were also set up though at the time deployment to these was still manually triggered. On the tenth day of work the team was able to demo the application to the CIO. Less than a month later, the PB Cloud environment became available at 11am, and within minutes we had the environment up and running, and were able to have users on the application to test by 1:00pm, only two hours later.

While these timelines are ahead of what is typically found in government environments, it is only a starting point. My personal goal has always been to match Google’s ninety minutes to create a prototype for Google Glass (reference How Google Works). If we were to have demo’d the application to the CIO after 90 minutes of having started work, the only remaining question would be to how to get that number down to 60 minutes. Never stop improving.

Model

The methodology outlined throughout this document is heavily borrowed from Team Topologies.

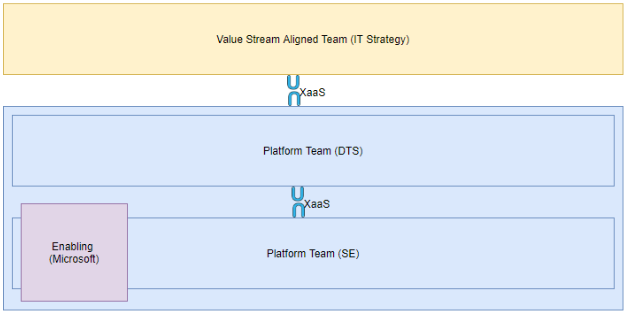

Figure 1: Team Topologies model

Text description of Figure 1

This image shows a yellow box at the top representing the “Value Aligned Team”. This box is linked via XaaS to a blue box representing the “Platform Teams”. Within the blue box, there are two platform teams that are also linked together via XaaS. In the case of the whitelisting application, the Value Aligned team is the IT Strategy team and the Platform Teams are DTS and SE. Both of the “Platform teams” are linked internally via XaaS. The SE platform team has one enabling contributor - Microsoft.

In a government context, the management model looked as follows

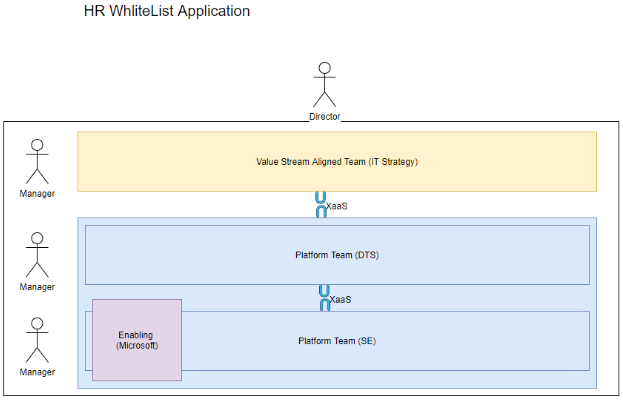

Figure 2: Government Team Topologies Model

Text description of Figure 2

Figure 2 is very similar to Figure 1. It shows a yellow box at the top representing the “Value Aligned Team”. This box is linked via XaaS to a blue box representing the “Platform Teams”. Within the blue box, there are two platform teams that are also linked together via XaaS. (in the case of the whitelisting application, the Value Aligned team is the IT Strategy team and the Platform Teams are DTS and SE). Both of the “Platform teams” are linked internally via XaaS. The SE platform team has one enabling contributor - Microsoft. In addition figure 2 also shows a stick figure director at the top and a box around the entire image demonstrating that a single director was responsible for the Value Stream Aligned Team and the two Platform Teams. Also on the left hand side next to the yellow and the blue box are three stick figure managers demonstrating that there was one manager for each of the 3 teams.

It should be noted that in our case, the separation between the DTS platform team and the IT Strategy team was not as well defined as it appears here. For example, throughout the project members from DTS attended the same standup meetings as the members of IT Strategy. Further more, the value stream aligned team was composed of programmers from the DTS team as well. The reason why we have represented the interactions between the teams above is twofold. Firstly, to represent how responsibilities would be split between teams if this solution were to scale. In our case, the application was simple enough, and the team small enough, to permit for a mixing of teams as we did. As one scales, this becomes less feasible (keeping in mind we want to reduce the cognitive load on team members, and keep teams as small as possible, while still being able to deliver the product). The second reason the interactions have been represented this way, is to communicate how the technologies interacted. In between the teams we see XaaS (Anything as a Service), because this is the terminology used in the book, Team Topologies, that I am heavily leaning upon. I have recently begun to use a different term – termination point. What is required is a termination point of responsibilities. In the case of our team, it was the termination point between members of the team, in large projects, it would be the termination point between different teams. A termination point is where the responsibilities of one group are transferred to another.

In our case, the termination points were specific branches in our repository. For example, all of the code prior to, and included in, a merge with the staging branch, was the responsibility of those focused on the application development work. Once the code was pushed to this branch, a deployment pipeline was responsible for deploying and hosting the application. This is noteworthy as the teams did not communicate through XaaS, per se, rather their work was coordinated through a termination point whereby the responsibilities were separated. This serves the same function as the XaaS in Figure 2. Namely, that a team’s work can be provided to others through an automated service, whether that be XaaS, or through some agreed upon termination point. Enforcing this is critical, as without it, deployment on demand can never be realized. This behaviour and way of working is where standards are required. Standardizing automated communication (while not specifying specific tools) is crucial for scaling automation and achieving deployment on demand.

For this project, an IT manager acted as the product owner for each of the teams, the Value Stream Aligned Team, the DTS Platform Team, and the second SE Platform Team. Please note this does not need to be the case. Actually, ideally it should not be the case. The product owner (the one responsible for prioritizing the work of the team) should be someone from business (albeit with technical knowledge or understanding). For further reading on why product owners should be from business recommended reading is De-risking custom technology projects.

One model often referenced is the so-called, and poorly named, “Spotify model”, which is only used here as a demonstration of an alternate model whereby product owners and managers needn’t be the same person. While this is generally the model that was used, it is abstracting away complexities that make it difficult for this model to work well in a government context. For example, the director at the top who is responsible for the management of the product is not the director for all of the teams in the box, though he is responsible for the platform, which makes reporting, hierarchies, and performance management a potential issue.

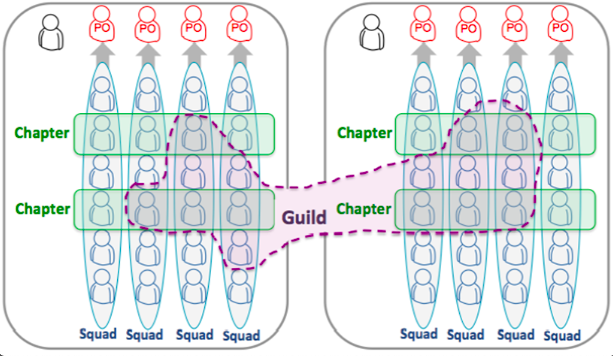

Figure 3: Spotify Model

Text Description of Figure 3

This image shows two groups of employees. Within each group there are four blue ovals representing 4 squads. Each of the squads report to a Product Owner. Across each squad there are employees with similar skill sets which are referred to as chapters. This image shows two chapters per group. The green boxes that represent the chapters go horizontally across the four squads with one employee per squad. There is a purple shape enclosed in a dotted line which represents a Guild. This guild includes members across the two groups as well as across the chapters and the squads.

In the above model, the squads are managed by Product Owners (POs) while the chapters would be managed by managers. The person located in the top left could be the director. In this case, they would play the role of the Product Manager. Once we merge the above model with the governmentized Team Topologies model, we could produce a more desirable model that looks something as follows

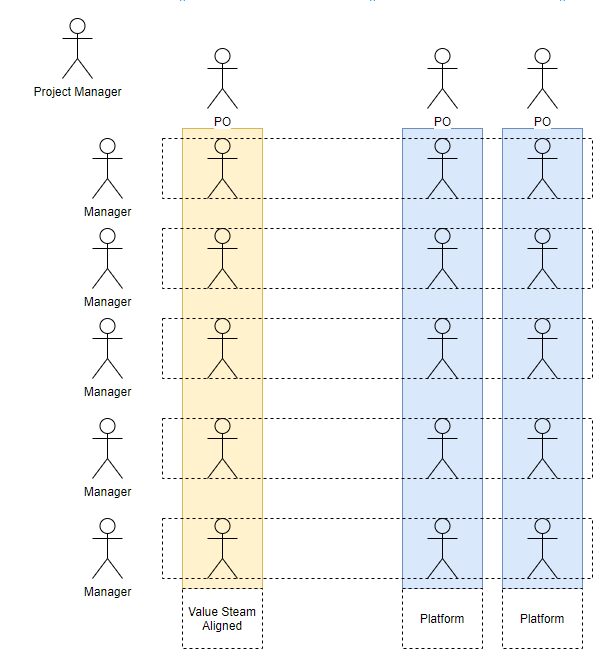

Figure 4: Final Government Team Topologies Model

Text Description of Figure 4

This image shows three columns. The left hand column in yellow represents the “Value Stream Aligned Team” and the two columns to the right of that in blue represent the Platform Teams. At the top of each column is a stick figure representing that team's Product Owner (PO). Within each column there are five stick figures. There are five horizontal boxes with dashed outlines going across each column containing one stick figure from each of the columns. The horizontal box demonstrates that there are people from each team with the same skill sets. Next to each horizontal box is a stick figure representing the manager for all those in the horizontal box which have the same skill sets. In the top left hand corner of the image is a stick figure representing the Product Manger who works with all the people represented in the diagram.

To make this easier to view we have removed details from the initial model, though it still applies. For example, regarding the method of communication, the ultimate goal would be for interactions between teams to be through automated means. That is, the interactions between teams are automated as a service that is provided to other teams. Further, there is the possibility to add enabling teams to the vertical teams identified here.

Why

Team Structure

This model is advisable over other commonly found structures as it builds in cross functional teams without dismantling the existing reporting structures within government. In order to rapidly deliver value to users, it is important that the team has all of the competencies required to deliver the product – business knowledge, application development, quality assurance, security, accessibility, and so on. This model allows teams with specialties to work embedded within teams, in order to reduce the number of context switches and handoffs between teams, which greatly reduce flow. Further, having a manager manage individuals with similar skill sets allows the manager to handle talent management for the team, while the product owner, who should be from the business (though they should have some level of technical understanding) focuses on the priorities for the product.

Application Structure

As covered previously, the aim is for automation (through XaaS or termination points) to be the overwhelmingly dominant method of communications between teams, especially for approvals. If even one team does not follow the standard of automating approvals, then deployment on demand, the ability to constantly deliver value to our clients, is dead in the water. Before cloud services, if a government employee wanted to have a virtual machine created in a data center they had to open tickets, create work request documentation, get approvals, send the work to another team after a series of handoffs, and so forth. With cloud technologies one is able to create the next generation virtualized technologies within minutes from anywhere in the world – no coordination with other teams required. This is the same model of service that teams should offer to one another within the organization, with the added benefit of still being colleagues and being able to reach out for help, support, or have more say in future services that are to be implemented.

Lastly, by creating a structure where the application team and the platform team are separate, this, via Conway’s Law, will promote an architecture where the systems are loosely coupled and independent from one another. Such an architecture allows for changes to be made independently for one another, which provides agility to each individual team. The team structure itself is intended to impact the architecture of the decision. As written in Accelerate, “The goal is for your architecture to support the ability of teams to get their work done—from design through to deployment—without requiring high-bandwidth communication between teams.”

Flow

Both of the above two sections have been focused on increasing flow of business value to users, through reducing handoffs between teams, and increasing the flow of information between teams through automation. In Figure 1 there is a purple team listed as an Enabling team. The use of enabling teams is another tool with which to increase flow. As discussed in the Team Structure section, the teams are designed to reduce handoffs and increase flow. As such, if there are missing competencies within the team the team must onboard those competencies into the team. One option would be to bring the expertise into the team permanently as a new team member, though this approach has two considerations one must take into account.

Is this a competency required for the duration of the project? If so, then perhaps a new addition to the team is the best decision. Otherwise, adding an additional member is not the optimal choice, as it is preferable to not interchange members of the team frequently. The aim here is to prevent the team from growing too large. Ideally agile teams should be kept as small as possible, given that the required competencies to deliver business value exist within the team. That means, all things being equal, it is preferable to enhance the skills of a team rather than onboard a new person, if this is an option.

If the team requires a skill that it is missing, this is where an enabling team comes it. The enabling team exists temporarily and collaborates with the team for a short time, in order to get the product team up to speed. During this time, the interaction method would be one of collaboration (this is in contrast with the interaction mode between teams in Figure 1, which is XaaS). If the team requires some functionality that requires very different skill sets than the ones existing within the team, this may be a natural fracture plane (a natural variable by which to split one large team in to two) whereby one could create a separate team, and then have the teams communicate via XaaS rather than through direct collaboration in an enabling capacity. For further discussion regarding the details of this approach, it is recommended to read Team Topologies, referenced to and linked to above.

It is for this reason, enabling flow within the team and upskilling the team to have the skills required to deliver business value, that champions were assigned (listed below). The idea of a champion is to have a member of the team focus on a given area and be dedicated to its improvement. For example, the accessibility champion would be responsible for (not accountable for, as the whole team is always responsible for the whole product) identifying and ideally rectifying issues pertaining to their focus. Ideally, if there is a team dedicated to accessibility, for example, the champion should reach out in order to identify existing best practices within the organization. Another option would have been to onboard an accessibility resource (using accessibility as an example, the same is true for any competency the team is lacking), however, we had difficulties finding a dedicated accessibility resource given the circumstances, so we designated a team member who was interested in a11y to dedicate time to learning and improving the a11y of the application.

Roles

Champions are roles where members of the team allocated the lion’s share of their time towards a given area, such as security or accessibility. It is important to note that in this model, the team is ultimately responsible for everything, so the individual themselves is not responsible for security – the team is. However, one individual within the team will pay particular attention to opening issues, documenting, and resolving the issues. The resolving part is important, as everything is about increasing the flow of business value to users. Documents do not increase business value to users, improving the solution itself does, which is where the focus should be. As per the agile manifesto, working software over comprehensive documentation.

Of course, the aforementioned description is that which ought to exist. During this project, we were unable to find a dedicated security resource with skills required (able to identify and commit changes to the code base). As such, we found two resources with the interest and skills required who were able to contribute on a best effort basis. The existing team attempted to assist by picking up work items that were suggested by the security champions, though could not be completed.

Conclusion

When the Spotify model became popularized it eventually led to Spotify doing a talk about how there is no Spotify model, as by the time people had seen the model, it had changed. It is important to note that no model used, or proposed, is intended to be static. For example, ideally the teams interact through termination points, though during the initial creation of the teams, it was treated much more as one team, relying on in person collaboration before the termination points were in place. Even after the automation was in place, from time to time more in depth collaboration was made between the teams. We could have re-created the model each time methods of collaboration changed, though this would become an arduous task. When working in this way what is more important than any particular technical standard is core principles (which one could call a standard, though runs the risk of overloading the term) that are strictly adhered to by all teams. This becomes the glue that holds the organization together, rather than restricting flow and innovation with standards. As written in Accelerate,

“The goal is for your architecture to support the ability of teams to get their work done—from design through to deployment—without requiring high-bandwidth communication between teams.

Architectural approaches that enable this strategy include the use of bounded contexts and APIs as a way to decouple large domains into smaller, more loosely coupled units, and the use of test doubles and virtualization as a way to test services or components in isolation. Service-oriented architectures are supposed to enable these outcomes, as should any true microservices architecture. However, it’s essential to be very strict about these outcomes when implementing such architectures. Unfortunately, in real life, many so-called service-oriented architectures don’t permit testing and deploying services independently of each other, and thus will not enable teams to achieve higher performance.”

This document is intended to contribute to the conversation regarding how the government could modify its approach to software development in order to transition away from the current siloed approaches that are commonly practiced to deliver software. Through the aforementioned approach the intent is to increase the organization’s ability to deliver value to Canadians, and improve their performance on the following four core metrics: lead time, release frequency, time to restore service, and change fail rate.

For further discussion as to why these metrics were chosen please reference DevOps Research and Assessment (DORA) - How to Transform and the book explaining the findings of the State of DevOps Reports (2019 PDF), Accelerate: The Science of Lean Software and DevOps: Building and Scaling High Performing Technology Organizations. For more discussions aimed at equipping government organizations to improve upon digital service delivery to Canadians, please visit the IT Strategy website, the authors of this document.